Today, I’m going to tackle a couple of related topics which seem to come up frequently in reader questions and comments – how is a cinema’s box office income distributed, and how much of it ends up with the filmmakers?

Today, I’m going to tackle a couple of related topics which seem to come up frequently in reader questions and comments – how is a cinema’s box office income distributed, and how much of it ends up with the filmmakers?

On the face of it, the first question seems simple: how is box office ticket income divided? However, it has proved an ongoing controversy, with some filmmakers claiming that cinemas keep most of it and some cinema staff claiming that they hand almost all of it over to filmmakers. I have heard people on both sides wax lyrical about how they have the raw end of the deal.

In order to answer the question, I have been speaking to a number of people in both the distribution and exhibition sectors in the UK and I think I have uncovered what’s really going on (and why both sides think they’re right).

The second question of how much money ends up with the filmmakers presents a different challenge: namely that the economics of each film are unique. However, most films go through the same basic steps of recoupment, meaning we can trace the common route between box office income and profit for the filmmakers and investors.

It might help us to look at the second question first, i.e. to get an overall picture of how money flows back to the filmmakers before we tackle the nitty gritty of cinema box office income.

The recoupment waterfall

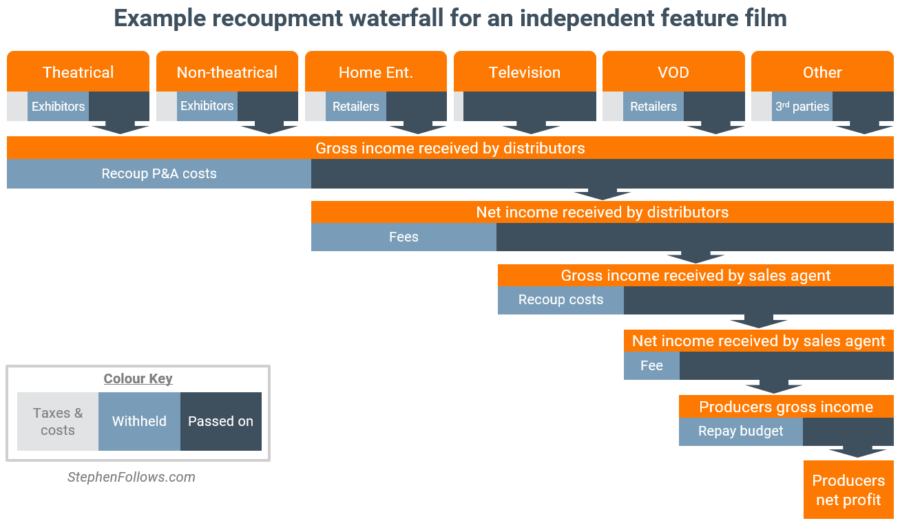

The way a film’s income is collected and distributed is known as the Recoupment Waterfall. Income comes in from a variety of sources and the money is then handed back to the filmmakers via a number of third parties. Along the way, these third parties can recoup the money they spent up front promoting the film and also charge a pre-agreed fee for their work. What’s left after a party has repaid costs and kept their fees will be passed down the chain to the next party.

Each film has its own unique waterfall but the majority will follow the following pattern (this chart uses a fictional film as an example):

There are a bunch of notes, definitions, and explanations which go with today’s graphics and examples. I have moved them to the end of this article for readability, so please have a look before emailing me in a state of confusion or outrage.

The final part of the waterfall is listed here as ‘Producers’ Net Profits’ and is when the remaining money reaches the bank account of the production company (or that of their appointed collection agent) and needs to be divided. Typically, the investors are repaid in full, and then the money is split 50:50 between the Investors’ Pool (i.e. profit for the investors) and the Producers’ Pool (i.e. the money shared with certain members of cast and crew who were assigned a share of profits). In many cases, investment deals can be slightly more complicated, such as:

- Each investor could have different terms, with some negotiating to be paid before others, or to get a fixed return rather than a slice of all profits in perpetuity.

- Major stars can demand a percentage of the gross income, rather than the net income in the Producers’ Pool. This explains why a star can earn millions on a “profit participation” deal, even when the film is not technically in profit.

- Some of the film’s budget may have been provided by tax rebates, meaning that a “$30 million film” may need far less than $30 million to ensure all investors are fully repaid.

Bring on the numbers…

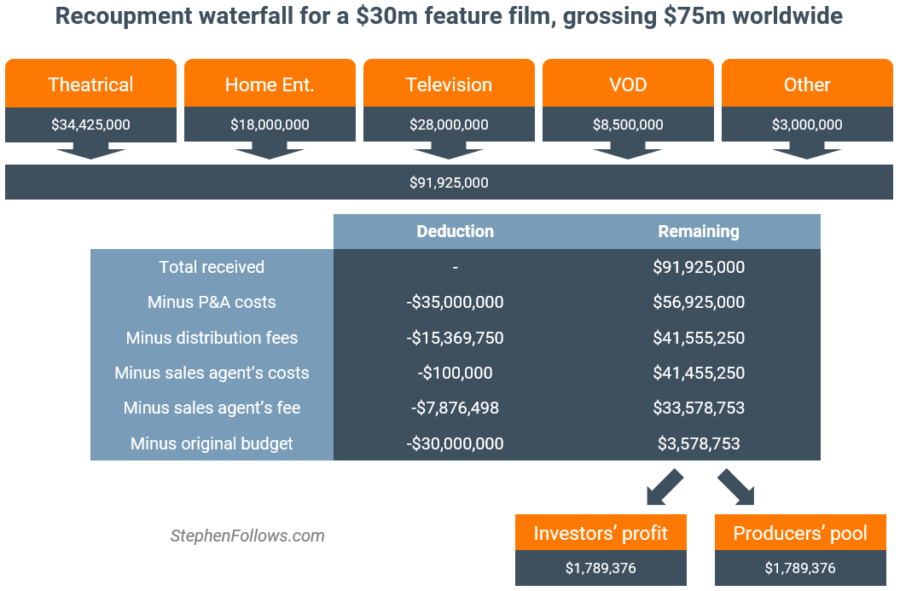

Let’s apply some numbers to this waterfall to see how the money flows (or maybe trickles is a better adjective, as in “Trickle Down Recoupment”). The actual fees will vary between films, so the ones I’ve used are the average fees of 1,235 film professionals I interviewed in 2014.

Let’s create a fictional film with a production budget of $30 million which grossed $75 million at cinemas around the world. The income figures below are the amount after deductions, such as sales taxes and money kept at the point of sale (i.e. the amount Odeon, HMV or Apple keep from each transaction).

In the example above, the investors had their initial money repaid ($30 million) and then received a further $1.8 million, representing a return of 106%. That’s very positive from the point of view of the film industry (i.e. there is actually profit!) but probably pretty poor from the point of view of traditional investors, especially considering the risk they took and the time before they were repaid.

In addition, the Producers’ Pool received the same amount, meaning that if an actor was promised 5% of the producers’ share of profits, then they would have received just under $90,000, on top of whatever up-front fee they were paid.

The final recoupment waterfall for a real film will rarely be as neat as my example. Some complicating factors could include:

- Each country the film is distributed in could have different tax rates and rules around distributing content.

- Each distributor may negotiate unique terms, including different P&A requirements and fee arrangements.

- Some distributors could pay a single fixed amount rather than a share of income (common practice in China, for example).

- A sales agent will often agree different fees for certain territories, such as a lower fee for the film’s home country, as that is regarded as an easier sale.

- Interest can sometimes be factored into money spent up front.

- Currency fluctuations will affect income.

What share of box office income do cinemas keep?

The keen-eyed among you will have noticed in the previous graphic that although our film grossed $75 million, we only received $34 million. This is because before we get our hands on box office income, there are two big deductions.

The keen-eyed among you will have noticed in the previous graphic that although our film grossed $75 million, we only received $34 million. This is because before we get our hands on box office income, there are two big deductions.

Firstly there’s tax. Sales tax varies wildly between countries, so I used a figure of 10% for this example (in the UK it’s currently 20%). Some countries also apply other taxes, e.g. India charges an Entertainment Tax of between 2% and 50%, depending on the type and scale of film.

The other big deduction is the amount the cinema (a.k.a. exhibitor or movie theatre) keeps. This is a rather contentious figure as different corners of the industry disagree vehemently as to what split is normal. When I interviewed over 1,000 film professionals in 2014, the average figure according to distributors was 49% but exhibitors reported it as 43%.

When I interviewed UK cinema staff in 2015, over a third claimed that high ticket prices were due to cinemas handing over most of the money. A common refrain was that sweets were expensive because cinemas “only get 10% of ticket prices so they have to make some money somewhere“.

In order to get to the bottom of this figure, I have spoken to a number of people ‘in the know’ in both distribution and exhibition in the UK. Some were quite senior and I am confident that the figure I built up is an accurate reflection of the UK market as it stands today. Here are the salient points:

The vast majority of mainstream movies released in the UK work on an income split, whereby the exhibitors and distributors split the ticket income after VAT (UK sales tax) is removed. Other models are sometimes used, including a ‘House Nut’ where the first £x of income is kept by the exhibitor after which income is split, or ‘Four Walling’ where distributor pays a fixed fee for the screen and keep all ticket sale income (minus handling fees).

The vast majority of mainstream movies released in the UK work on an income split, whereby the exhibitors and distributors split the ticket income after VAT (UK sales tax) is removed. Other models are sometimes used, including a ‘House Nut’ where the first £x of income is kept by the exhibitor after which income is split, or ‘Four Walling’ where distributor pays a fixed fee for the screen and keep all ticket sale income (minus handling fees).- There isn’t one universal figure. The split between exhibitors and distributors can be different for each film and is a point of negotiation when discussing the deal.

- The split changes over time, in favour of the exhibitor. Distributors can usually negotiate a better deal in the opening week or two and so the longer a movie plays, the more the exhibitor will keep from each ticket sold. For example, a distributor may receive 55% of ticket sales in weeks one and two, 50% in week three, 45% in week four, right down to a base of 30% in the final weeks.

- Only the biggest movies commonly claim more than 50% of income. When they do, it is almost always from a major distributor and only in the first week or two of the film’s run. As one expert put it “a 55% split in favour of the distributor is generally regarded as a great deal and some recent major releases have achieved that“. I understand that recently a certain expensive sci-fi movie from a major studio managed to secure 65% of income in its opening week but this is regarded as exceptional.

- Distributors of independent films typically receive between 28% and 35% of income. This means that for some ‘specialist’ titles (art house films, small foreign language films, documentaries, etc), the exhibitors are keeping up to 72% of the ticket sales. That said, most of these titles have a minimum guarantee attached, to prevent the distributor from getting pennies. A typical deal is “35% vs an MG of £100”, meaning that the exhibitor must pay the distributor either 35% of the box office or £100, whichever is the greater.

- The UK has among the highest exhibitor splits in the world. This is partly due to the relatively high cost of media advertising in the UK and also due to historic deals between British cinemas and distributors.

- The power in the sector is shifting – in both directions. As more movies than ever before are being pushed onto the UK theatrical market, exhibitors have increasing power to demand better terms from all but the biggest movies. However, at the top-end, the tentpole studio movies are bigger than ever before (budgets and marketing spend), meaning distributors releasing major mass-appeal titles are able to secure much better than average terms in opening weekends’. The smaller films are being squeezed by exhibitors and the big films are squeezing the exhibitors.

Where did the myth of cinemas only keeping 10% of box office income come from?

I asked around and it seems that it’s got its origins in a real event, but is a case of misunderstanding. In the words of someone senior in UK distribution:

I asked around and it seems that it’s got its origins in a real event, but is a case of misunderstanding. In the words of someone senior in UK distribution:

The “90%’ figure quoted probably relates to a rare deal a while ago with a major cinema chain, which applied it to the first tranche of income, in the form of a ‘house nut’. It’s extremely unlikely that a 90% deal has ever been agreed for all the box office income for a movie”.

On the other hand, someone from another part of the distribution chain said:

Personally I think you’re being a bit too overly diplomatic with the reason for the 10% thing! Exhibitors in general have a bad view of distributors taking all the cash… and also because they use it to justify their concession charges to customers

As we saw with the differing opinions on average fees from my survey, it’s unlikely that everyone from the industry will be able to agree on one interpretation of ‘common practice’. However, I’d like to think I was able to get some clarity on this issue and bust a few myths.

I’ll leave you with an old industry joke which Geoff Greaves, owner and operator of the Merlin Cinemas chain, told when picking up his Exhibition Achievement Award at last October’s Screen Awards. He described turning up to a coffee meeting, finding no cream to add and declaring “The distributors must have got there first”.

Further reading on box office income

If you’re interested in learning more about the topics mentioned above, then you may enjoy these other articles:

- What are average film distribution fees?

- How movies make money: $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters

- How films make money pt2: $30m-$100m movies

- How much does it cost to release a film in the UK?

- The thoughts of UK cinema staff

Notes

Below are some definitions and notes to go along with the recoupment waterfall graphic:

Below are some definitions and notes to go along with the recoupment waterfall graphic:

- The income boxes are not to scale. i.e. Non-theatrical income is a fraction of Theatrical income but is shown the same size on the graphic for readability.

- ‘Other’ income includes merchandise, movie tie-ins, novelisations, soundtracks, etc.

- P&A stands for Prints and Advertising and these are the costs the distributor pays to bring the movie to cinemas and promote it to the general public.

- The example is an independent film. Films made by studios are typically distributed by the studio’s own distribution operations around the world. In theory this could remove the third party fees charged by sales agents and distributors but in practice the studios charge themselves similar fees. This is partly because the studio distribution companies are legally separate entities (to comply with anti-trust laws) but also because it reduces the official profit, thereby reducing the amount they have to pay out to people with a profit share. In smaller markets, studios may use third parties where they’ve judged the costs of running their own permanent distribution operation is too high.

- The example of the working waterfall is fictional. Grossing $75 million worldwide on a $30 million budget is a middling box office tally. Other movies of the same budget include Steve Jobs (which grossed $35m worldwide), Entourage ($49m), The Next Three Days ($67m), Sicario ($78m), Deliver Us From Evil ($88m), Kick-Ass ($98m), and La La Land ($272m so far).

Epilogue

I am very grateful to the people who helped me with this article. I spoke to a number of industry professionals, some very senior, in order to get to the bottom of how this part of the industry functions. Most were hesitant about speaking out until I agreed not to print their names. It seems that there is a real taboo in the distribution sector about going on the record with things like the terms of deals. Some of this may be down to non-disclosure agreements and UK competition law (which places limits on what commercial information companies can share with rivals) but most seemed to stem from a more general sense of secrecy.

Interestingly, almost everyone I speak to in the industry decries the culture of secrecy and opaqueness but few are willing to be the first to put their head above the parapet. And I understand that – being one of the few people to share private or commercial information can’t be fun. Hopefully, over time we can change this so we can all learn from each other and work together to help the industry function better.

Comments

This is tremendous – thank you. The bit about big studios splitting themselves into different entities to reduce profit shares is particularly interesting. It may help to explain why poor David “Darth Vader” Prowse never got any residual payments for the “special edition” reissue of Return of the Jedi despite a worldwide gross of $88 million.

He said in an interview with Equity magazine in 2009: “I get these occasional letters from Lucasfilm saying that we regret to inform you that as [the special edition of] Return of the Jedi has never gone into profit, we’ve got nothing to send you.”

I’d love to know more about those profit share deals that Eddie Murphy memorably called “monkey points”.

It’s certainly a topic on my list to cover. In the meantime, here’as a piece I wrote way back in 2013 which touches on it a bit https://stephenfollows.com/much-tom-cruise-paid/

There’s always a point at which folks get shy with the detail, but well done. The separate entity wheeze is not limited to the majors, however. Many independent production companies on this side of the pond have subsidiaries or associated ‘sales’ or distribution arms which are used to funnel box office and sales income against which a lot of continuing overhead, marketing and ‘cost of sales’ are deducted.

When ‘soft money’ (subsidy finance on which there is less pressure to make a return) and issues like deferrals or ‘shares’ as finance elements are added to the mix then it can all get very murky. You will sometimes see festival seminars on “how we made ‘whatever the title’ for no money”, but you never, ever see seminars on “how we shared the money” when ‘whatever the title’ was a huge success!

Superb. Illustrative and Insightful.

Quick questions – who bears the P&A costs and risk?

What is the role of the sales Agent

Excellent analysis, overview, data and graphics as always. Worth highlighting just how much the home entertainment market (ie packaged media – DVD retail and rental) has collapsed, to the point where it has gone form being the largest earner to third behind theatrical and TV. Blue-ray has not replaced it and streaming (Netflix, Amazon, other SVoD) does not make up the difference in fourth place. Studios are suffering DVD withdrawal symptoms, hence the flirtations with shortening the release window.

I’m confused, sorry. Isn’t the gross $91.25 million, not $75 million??

The “box office gross” is the amount collected via ticket sales in cinemas. However, we (as filmmakers) don’t get that. Taxes and exhibitors take a chunk of it and in this fictional example that left with around $34m from that “gross”.

Then we add it together with the money we got from other sources (DVD, TV, etc) and that’s where the $91m figure comes.

Does that help?

Yes, thanks. I was looking for the $75 million within the graphic, and couldn’t find it. Now I understand why! Having my coffee before reading the article would likely have helped too…

quite accurate the standard for big titles is 60 percent,with Disney having a scale up to 60 percent depending on cost of production and take.interesting to note that there two star wars films charged 55.fox charged 70 percent but where just distributers not the production company

Stephen

Great piece, thankyou. Just letting you know that neither of my very much working email addresses was acceptable to your signup tool, not sure why. I am in Oz but that should not be a problem. One of them was apple’s me dot com network…. pretty mainstream. So I can’t get your email alerts, methinks.

Glad you enjoyed the article. Sorry to hear the sign-up tool is buggy. Can you use the contact form to get in touch so I can find out more? I’d like to get to the bottom of what’s happening so I can fix it. Thanks!

For the home ent (18mm), TV (28mm), VOD (8.5mm), and Other (3mm) are those gross revenue numbers for each category or less distributor’s fees?

Hi, Stephen,

I had wanted to respond to this when it first came out, but it has taken me some time to find the space to do it. I generally like a lot of what you do, but I think there could be one, maybe more misnomers in this piece. I will focus on the recoupment chart. Typically, a distributor would not deduct costs before their distribution fee, as that has a negative impact on their ability to grab all the money they can. In my experience, and that of others I checked with, it is the fee first, and then the expenses, enabling the distrib to grab a percentage of a larger pie in fees first. Below, I have duplicated yours, and then my understanding of it. Does this more accord, or do you feel it is more like your original?

It appears I cannot drop an image into the reply window, so I will email them to you.

Jeffrey N. Hardy

Thanks, Great info.

You mentioned that Distributors get a percentage of ticket sales, but i have a question regarding what the ticket sale includes. Is it just the admission fee, or does it also take into account additional services (Scenarios below).

Scenario 1:

Normal Cinemas: $18

Extreme Screen (Bigger screen and sound): $23

Luxury (reclining chairs and ability to purchase food): $35-40

Would the Distributor get % of the entire ticket price or just the admission fee? It is the same movie, but clients pay for bigger screens, louder speakers and better chairs.

Scenario 2:

If a cinema was to offer a package deal containing blanket rental ($7) + ticket ($18) for $25 in a normal Cinema, would the distributor get a % on the ticket @ $18 or the whole $25?

I appreciate your help in clarifying this for me.

Hi Logan

Thanks for reaching out.

I don’t know the Australian system first hand, but if it’s anything like the others then all the money raised for the ticket prices is included in the distributor’s Film Rental calculation – nothing is taken off the top first (such as extra charges for IMAX etc).

The only exception might be if you’re also buying 3D glasses at the same time, but in my experience they tend to be billed separately.

Hope that helps

Stephen

Hi Stephen, thanks for this informative article. As a followup to the question above – what happens when the exhibitor discounts the tickets? For example, AMC and Regal has these $5 or $6 per ticket days. In this case, would the studios simply get $3 (assuming 50% of $6) or would they still get $4.50 (assuming 50% of the average $9 ticket price) and the exhibitor would simply only get $1.50 per ticket instead of $4.50?

By default the split is based on price actually paid, not an average or standard price. But it’s worth noting that major distributors carve out their own deals on a per film basis so it’s conceivable that if a cinema kept cutting prices then distributors may look to counter that in future deals.

Big long term deals (such as the two-for-one deal with Compare The Market) work on the basis that the organisation offering the deal pay the cinema a pre-agreed fixed price for each “free” ticket used. The spilt is then based on that.

This was a great post and very informative. In the UK some cinema chains (like Cineworld with the “Unlimited” or Odeon with “Limitless” memberships) offer an all-you-can-watch subscription model.

I imagine that this income is split in the same way as a regular admission, but the income would divided by the number of admissions by a member within a month. I’m surprised distributors might be happy with this potential risk and inconstant income per admission. Any thoughts?

Hi Steven, you’ve probably noticed the recent #BoycottMarvel #BoycottDisney trends. Some of it due to Marvel’s handling of the James Gunn situation and more recently the influence the Marvel Head has on Veterans Affairs in the USA. Anyway, a big entity like Disney/Marvel is always doing something to piss of someone.

I’m researching a post I’m writing about how to boycott a studio’s movies, but still watch the movie. Because let’s face it, I’m going to see End Game, no matter what. 🙂

After reading your post here, and a number of others, the best I’ve come up with is that ticket income is negotiated differently for each film, but generally speaking, the longer you wait to see a movie after it’s release the more money the cinema makes and the less money the studio makes. Is that a fair generalization?

Hi mates, its fantastic post about educationand fully defined, keep it up all

the time.

Hi, I’m relatively new to the cinematic distribution and it’s a minefield! This is really helpful to people who don’t have many contacts in the industry and not many places to turn to for information. Thank you so very much

Thank you stephen, very useful information.

Very simple explanation of a complex subject. One thought though, now films are distributed. digitally, wouldn’t the ‘Prints’ cost in the P&A be significantly reduced?

Not sure what bearing this has though, especially in the, as you say, opaqueness of the system.

Geoff

Hi Stephen,

Fantastic read, thanks.

I’ve noticed in the UK, in the last few years, there seems to have been a reduction in ticket prices by a few of the big chains, along with an increase in food costs. I’d guess the ticket price reduction is a reaction to competition from streaming and especially how quickly films become available to rent online.

Do you know if this has changed the model in the UK more towards the fixed price options and away from a split? Or are distributors getting a higher proportion of the split?

Thank

Stephen

Fantastic research/post and highly educative, Stephen.

Do you think smart contracts (on a blockchain) could simplify this value chain and reduce margins of middle men, so that producers receive more?

Hi Michael

Generally, I see a lot of technological solutions being proposed to human problems. The reasons the system is stacked against indie filmmakers are to do with a lack of ways to make it fairer. So a new tech is unlikely to address the core issues.

Hi Stephen, brilliant article, like so many on your website.

May I ask for your insight: Since the publication of this, would “Home Entertainment/DVD” not have plummeted entirely?

But would selling rights to Netflix, Amazon Prime etc. have made up for it? Or is making movies on the same budget just much, much less profitable than it was 2016/17 due to this trend?

Thanks for this hugely informative article. In the fictional example, if the P&A costs are the distributor’s costs, are the distribution fees the distributor’s profits? That would be 8 or 9 times more profit than the “producer’s pool” going to anyone who was creatively involved in making the film…that seems deeply unjust.

Hi Stephen,

Love your articles. Maybe you can help and happy to pay for your insights. I am aUK based Independent Producer partnering with an India streaming platform. I have been asked to produce a set of global projections for a tentpole movie costing approx $130 million, and I’m not sure where to start!

I have this set of percentages which may be useful,

US/CANADA – 29%

FRANCE- 4%

CHINA – 16.6%

SOUTH KOREA – 3.4%

JAPAN – 5.9%

GERMANY – 2.8%

INDIA- 4.6%

AUSTRALIA – 2.5%

UK & IRELAND- 4.6%

MEXICO – 2.3%

But my main concern is that figures for streaming revenue versus box office may not exist yet.

Any help or advice you can give will be greatly appreciated.

Thank you and all best wishes, Chris Rose.