Last week, I shared research I have conducted into the number of short films made over the past two decades. I focused on live-action shorts which had played at least once at any film festival.

Last week, I shared research I have conducted into the number of short films made over the past two decades. I focused on live-action shorts which had played at least once at any film festival.

While production levels are interesting, they were not the original reason I conducted the project. I was responding to requests to look at the gender of short filmmakers.

I have studied gender in the film industry a number of times in the past (links at the end of the article) but only briefly with regard to short films. Shorts are an important data point to track when seeking to build up an accurate picture of gender among filmmakers.

For many filmmakers, short films represent the leap between their final stage of formal education and making feature films. When I interviewed over 100 working film directors in 2016, around a third cited short films as a vital part of their journey into professional directing.

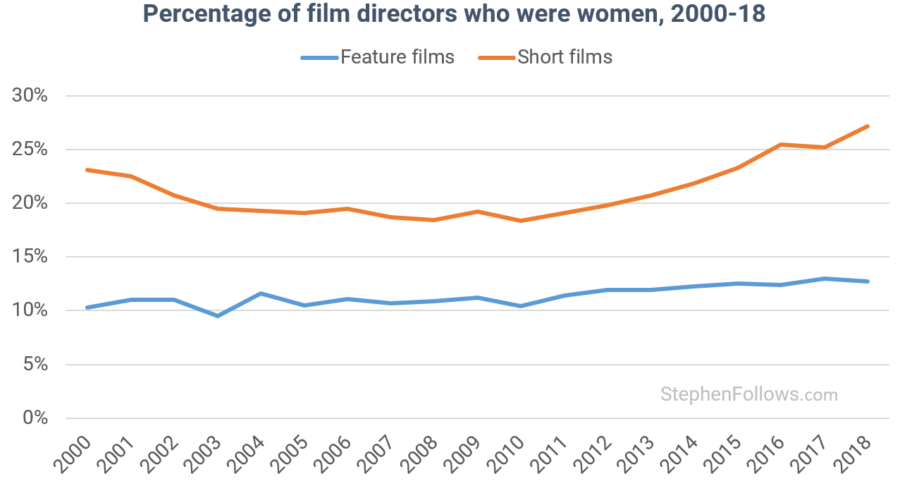

My past research has shown that film schools have pretty much equal numbers of male and female students, whereas men massively outnumber women in feature film writing and directing (under 13% of feature film directors were women in 2018). In addition, my research has shown that as film budgets rise, the number of women in key roles falls, suggesting that the more the film industry is involved with a production, the more men are favoured over women.

Short films do not need the kind of industry permissions/support features do, they cost a fraction of a feature film budget and are largely self-financed. Therefore, it could be suggested that short films sit somewhere between the open nature of education and the gender-skewed professional film business.

What percentage of short filmmakers are women?

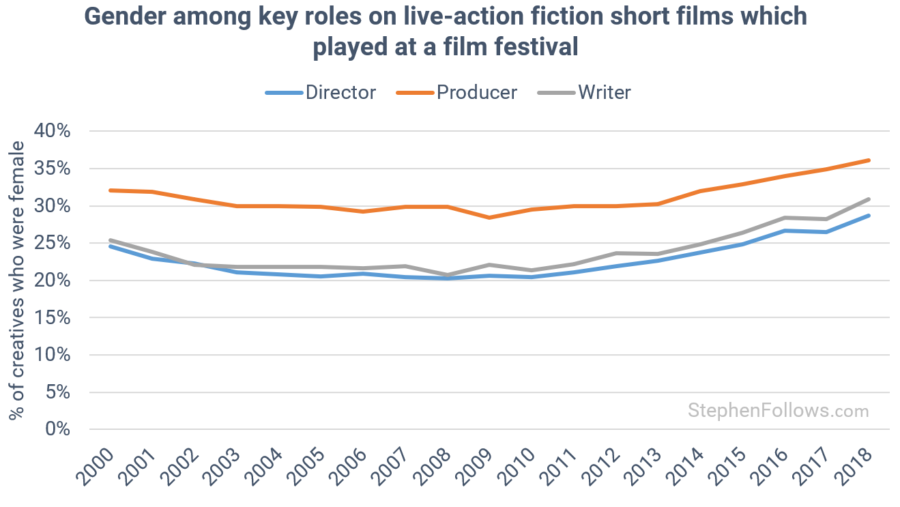

Over the nineteen years I studied (2000-18), 21.3% of short film directors were women, along with 31.2% of producers and 23.4% of writers. The years with the highest representation were the most recent ones, with 2018 being a high-point for all three jobs.

When we compare this to the employment of female directors on feature films over the same time period, we can see that short films have always had a significantly greater percentage of women at the helm.

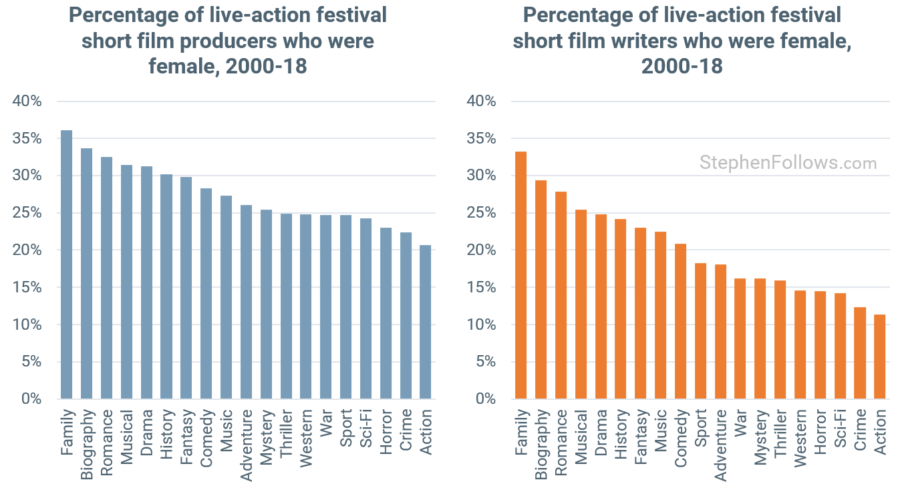

Gender of short filmmakers by genre

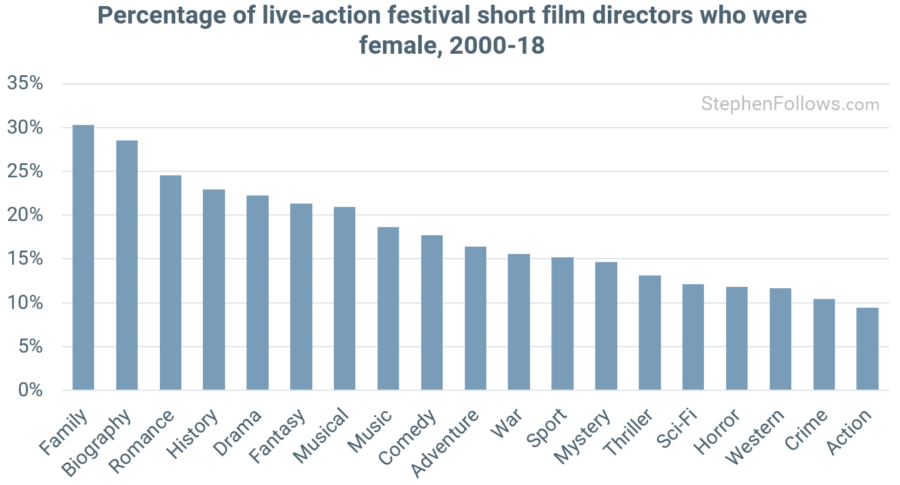

Family films and biographies are the most likely to be directed by a woman (30.2% and 28.5%, respectively) with crime and action films the least (10.5% and 9.4%).

The pattern is extremely similar for producers and writers.

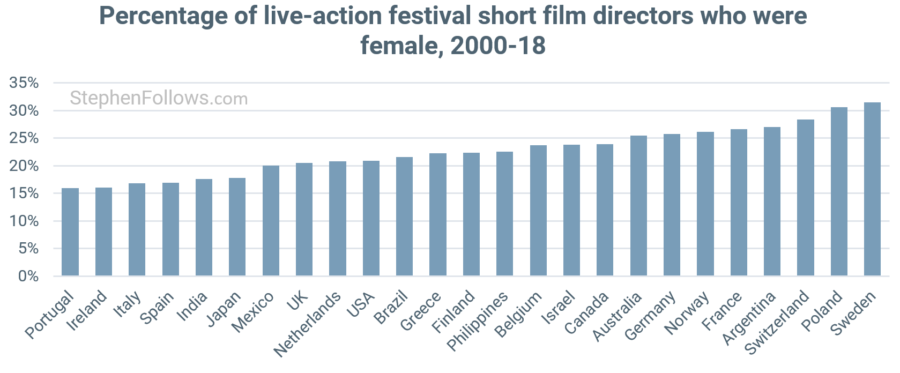

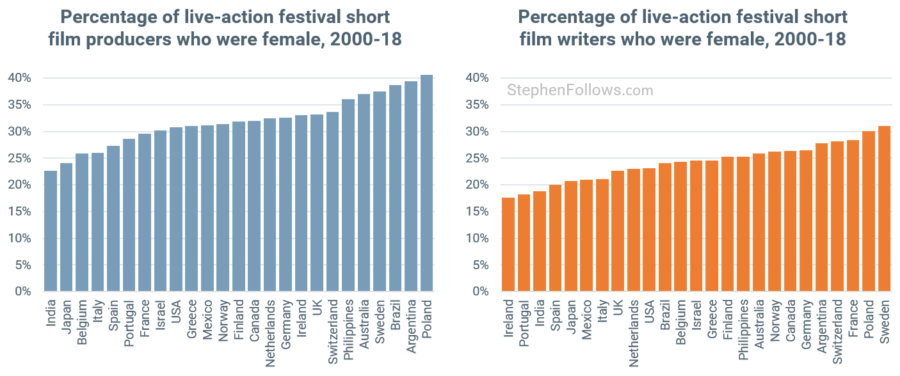

Which country’s short filmmakers have the greatest representation of women?

Gender representation also differs significantly by the country of origin. Short films made in Sweden and Poland have the highest percentage of women (31.4% and 30.6%, respectively) with Portugal and Ireland having the lowest (15.9% and 16%).

Note: these country charts are looking at the top producing nations and so ideas of ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ relate to the countries listed, not to all nations of the world.

One last thought – are film festivals biased?

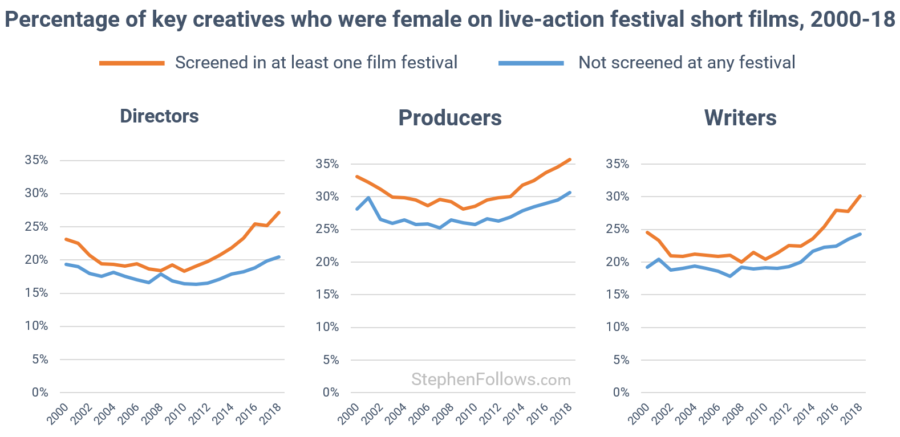

As discussed last week, I focused on festival films in order to provide a more comprehensive and robust dataset. Without this criterion, the database would include all sorts of short-form content we don’t typically think of when referring to “shorts”, such as music promos, TV spots and online videos. During the research process, I logged almost half a million such short-form productions, before applying the festival criteria which cut it down to around 90,000.

Whilst I chose not to use the full dataset, it does give us a chance to test a thought I had during the project – are film festivals adding to the male skew shown above?

This is a topical concern as only a few weeks ago, Stephen King came under fire for saying that he does not take diversity into account when he votes for the Oscars. His point was that such contests should only take into account the art of the films, whereas other commentators made the case that it is the duty of awards, festivals and professional bodies to be more active in redressing diversity imbalances in the industry.

I’m not going to express a view on this debate but it does remind us that when we’re looking at films, they may already have crossed a number of filtering steps. In the simplest terms, the filmmakers have chosen to pursue a career, the industry has selected some projects to be made and then festivals have chosen their line-up from submissions. Ideally, we would be able to split apart the data at each major stage along the way in order to see what is causing the male skew in the final dataset of “festival films”.

So I returned to the full dataset and looked at how female representation differs between all live-action short-form content and live-action festival films. This crude test shows us that festival films are more likely to be made by women than those which did not reach festivals.

We can’t measure the quality of these films, nor how many fit the entry requirements of each festival, so we shouldn’t lean too heavily on this result. Many factors are at play and this alone is not enough for us to not categorically say that festivals do have some kind of selection bias when it comes to gender. However, we can say that that short films at film festivals have a better representation of female filmmakers than a wider dataset of all short-form content.

Notes

You can read more about my methodology in the Notes section of last week’s piece.

To determine a person’s gender, I used publicly available data, pronouns (such as in biographies) and first name analysis (i.e. if 99% of people called Daniel are male then I have regarded every Daniel with an unknown gender as male). I appreciate that this research takes no account of gender fluidity or other forms of self-identification. That’s not a conscious choice but rather a consequence of doing research at this scale. If anyone can suggest a way of taking this on board in the research process then I am very keen to hear it. Please drop me a line and we can talk it through.

If there was anyone for whom I could not reliably determine a gender, then they were not included in the charts which show a percentage split between male and female crew members. Although this is not ideal, I have no reason to think that these people skew towards one gender over another, and they were also a small percentage of my overall dataset. For the vast majority of the period I studied, people are extremely likely to have publicly identified in a binary manner, no matter their true feelings or identity. This research speaks to how people are judged from the outside and it’s the public-facing gender identity that matters most when it comes to discrimination.

The countries stated relate to the origin of the film, not the filmmakers. I provided data for the top 27 short film producing nations for whom I have reliable data. Films can come from more than one country.

In a bit of serendipitous timing, next month the Short Film Conference @ Clermont-Ferrand has a panel discussion on this very topic. “50/50 BY 2020: GENDER EQUALITY IN THE SHORT FILM INDUSTRY” takes place at 2pm on Monday 3rd Febebruy 2020 in Clermont-Ferrand, France.

If you want to read more on gender in the film industry, here are some more articles you may enjoy stephenfollows.com/category/women-in-film

Epilogue

I have kept this article factual, rather than pushing my opinions or thoughts. This is for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I don’t feel I understand all of the effects at work enough to definitively state ‘This is what’s happening’. Secondly, even if I did, this is not a topic where one person gets to state their view as fact. So I’ve opted to keep the data away from the subjective interpretation of that data.

This is where you come in.

I would be delighted to hear the views of readers in the comments below, from all perspectives and with all viewpoints. I would ask that we keep things civil and respect everyone’s right to have their own reading of the data.

As a couple of jumping-off points, here are some questions:

- Is this a question of employment or of who controls our cultural output? Is the goal to have equal access/treatment for people of all genders, or are we looking to have the wider population proportionally represented in our filmmakers? We could imagine a thought exercise whereby one gender is twice as keen to become filmmakers as another. Given equal access/treatment then we would end up with twice as many filmmakers from the former than the latter – i.e. equality of opportunity. However, given the same thought exercise, we could say that it’s more important that filmmakers represent those two genders in similar numbers, given that the population is split equally.

- Do different genders have the same interest in filmmaking – and how would we know? If we decide that equality of opportunity is our goal, then it becomes important to know what the ‘natural’ level of interest is. If one were to focus on the film school data then the conclusion could be drawn that interest in filmmaking is consistent across genders. Conversely, it could be argued that short films provide a better measure of interest as they are closer to the act of filmmaking but with very few of the film industry structures which are at fault in features. Each of these two data points indicates wildly different interpretations of how much current industry employment is down to taste or bias.

- What does the differing levels of representation across countries mean? A further interesting result from this research is the different levels of representation across countries. If hypothetically, men were much keener to be filmmakers than women, we would not expect to see the wildly different results across borders. While it’s certainly true that culture plays a factor in people’s preferences, it seems a stretch to imply that living in Sweden is enough in itself to make a woman twice as keen on filmmaking than a woman living in Portugal.

- How should we interpret the gender differences in genre? A Directors UK study found that female TV directors are more likely to be siloed into shows traditionally seen as “female” i.e. daytime TV, children’s shows and lifestyle. This is reflective of a trend in the film industry whereby men have a greater opportunity to make the bigger and more “important” productions. And yet, both filmmaker and audience data suggest that there are some differences between levels of interest in certain genres and gender. A case in point is the extreme differences between female representation among directors of ‘family’ and ‘action’ short films (30% and 9%, respectively). How can we disentangle willingness to make films of a certain genre and biased opportunities to do so? And, to go one level further, how can we tell how much of the differing levels of interest are due to cultural stereotypes (within the film industry and ideas of gender more widely) and the historical lack of diverse role models?

- How can this data help us discover examples of best practice around the world? If we are looking to move towards gender parity then what lessons can be learnt from the countries which show high levels of female representation, such as Sweden, Poland and Switzerland?

To be clear, the questions above are not my opinion, nor are they hinting at any particular answers. I’m keen to have a healthy debate on the topics and thought it might be helpful to provide some prompts.