In the most recent issue of The Hollywood Reporter, they covered the efforts being made to increase the representation of women in below-the-line roles.

In the most recent issue of The Hollywood Reporter, they covered the efforts being made to increase the representation of women in below-the-line roles.

As part of this coverage, I was asked to crunch the data on the number of women working in specific film departments.

So I built a dataset of all feature films released in US cinemas over the past twenty years and sought to calculate the representation of women in below-the-line roles. There is much more about my methodology in the Notes section at the end of this piece.

The big picture

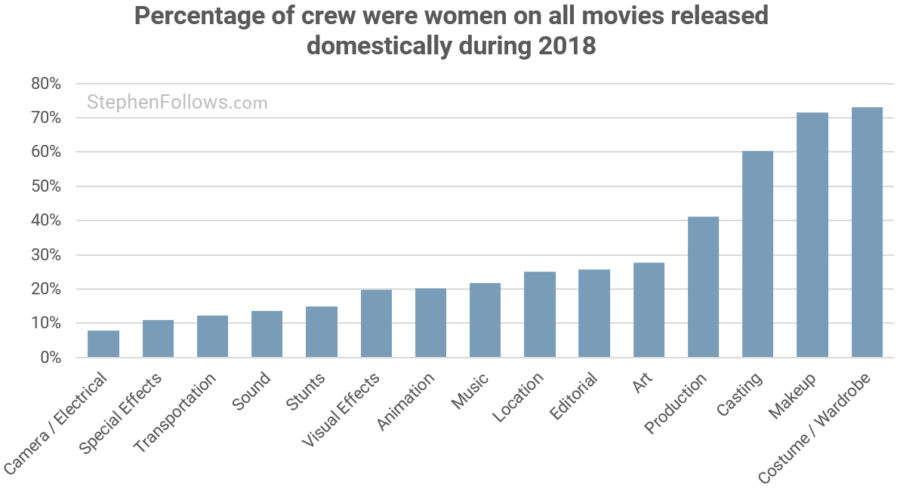

Let’s start by looking at the big picture for films released in 2018 and then focus in on a few of the departments over time.

Of the fifteen departments I looked at, only three had a plurality of women – casting (60% of crew members were women), make-up (72%) and costume (73%). At the other end of the spectrum were transportation (12%), special effects (11%) and camera/electrical (8%).

How has this changed over time?

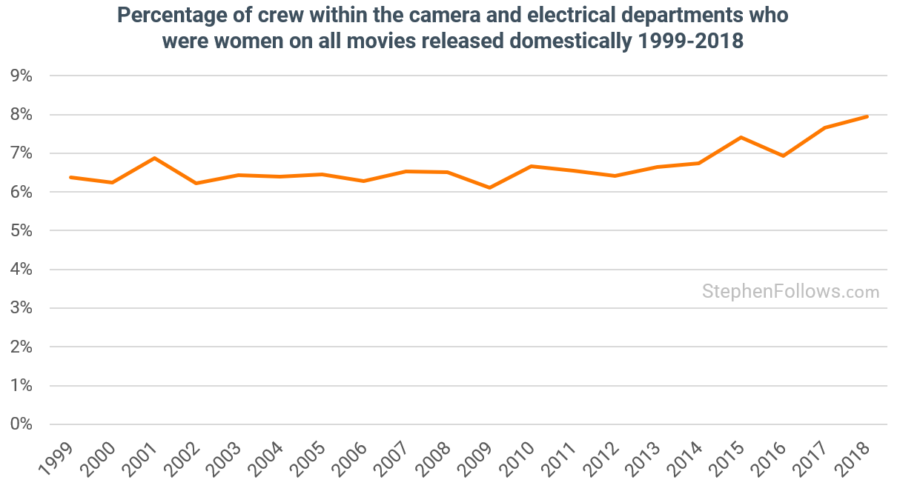

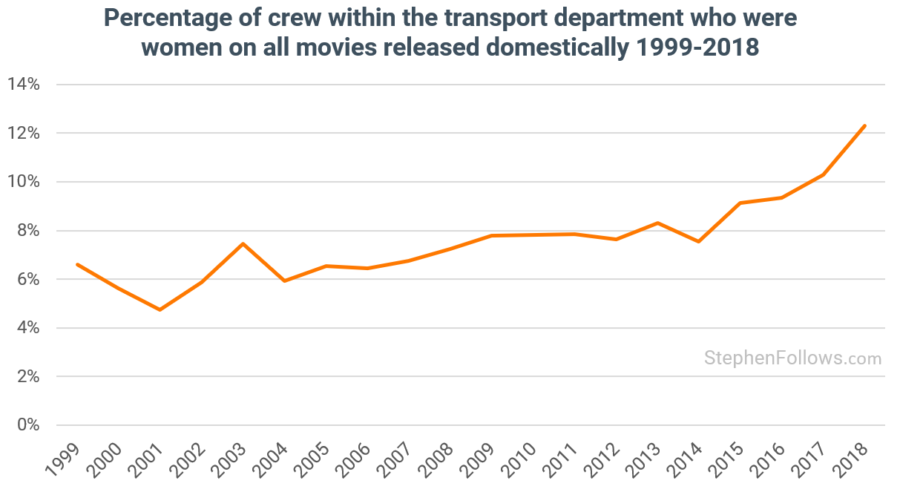

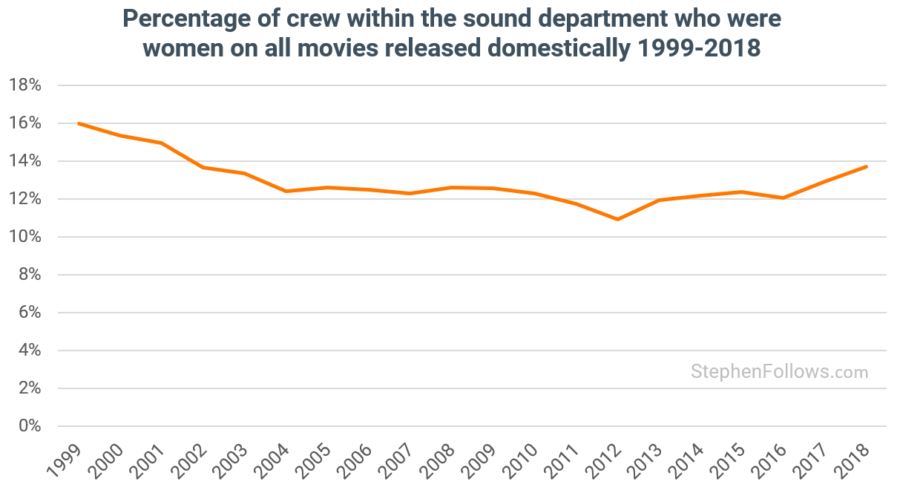

To get a sense of how the picture is shifting, I’ve picked out three departments at the lowest end as each tells a slightly different story.

With the camera and electrical departments, the picture has been fairly static for most of the past two decades, with a slight uptick in the last few years.

The transport department has seen a significant increase, more than doubling representation (albeit from a low starting point). The worst year in the past two decades was 2001 in which 4.7% of the transport crew were women whereas the best year was 2018 at 12.3%.

The reverse is true for the sound department. Between 1999 and 2012, representation dropped from 16.0% in 1999 to 10.9% in 2012. Since then we’ve seen an uptick, with the figure standing at 13.7% in 2018.

The types of films being studied matters

When these stats were published by The Hollywood Reporter they unfortunately misreported them. They said that the figures related only to US films and those grossing over $1 million, rather than all films released Domestically. I’ll go into more detail as to why this matters at the end of this article but for now, let’s look at the difference between those two types of films.

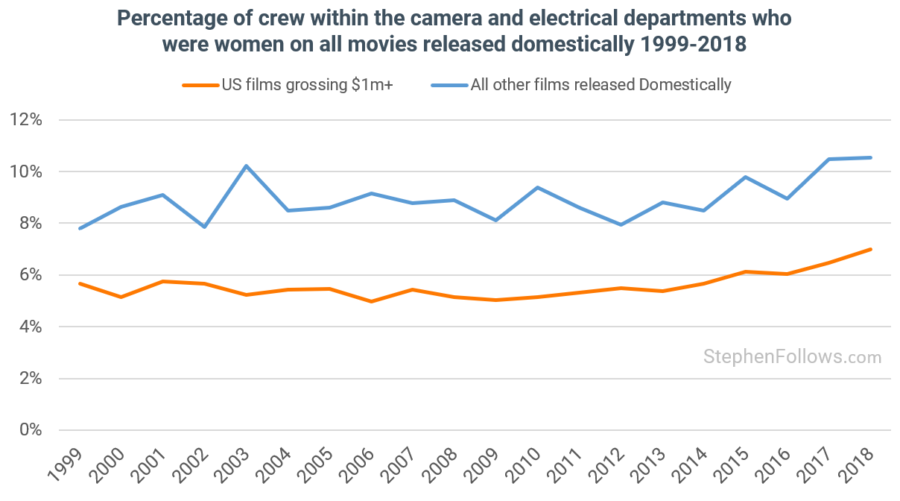

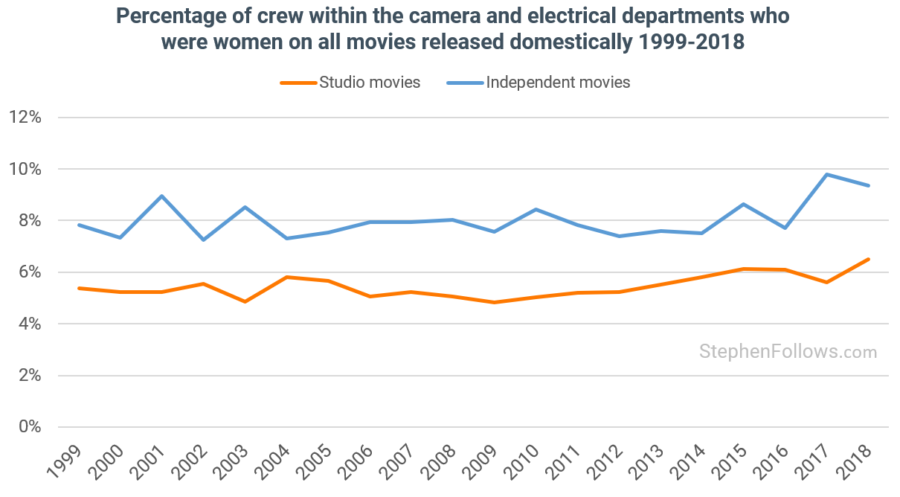

I’ll focus on the camera and electrical departments as it’s the one with the poorest record of female employment of those mentioned above.

As you can see in this graph, women are more likely to be hired on films which gross under $1 million than those which gross over $1 million.

This pattern is almost identical to what we find if we split studio releases from independent releases. This is because (a) studio films are more likely to be US films with a gross of over $1 million; and (b) because the same trend is at work, whereby bigger films feature fewer female crew members.

Further reading

If you want to read more about gender in the film industry, you may enjoy (well, perhaps “enjoy” is the wrong verb) the following articles:

- The gender of Directors of Photography (gender stats at the end of the article)

- What percentage of film producers are women?

- Are women less likely to direct a second movie than men?

- My study of film directors in the UK film industry

- Gender diversity among film professionals working in sales and distribution

- My study into gender inequality among UK film and TV writers

Notes

The data for today’s research came from a number of places, principally IMDb, The Numbers, Wikipedia, Box Office Mojo and OMDb. My dataset is of all fiction feature films made and listed on those sites. Genre classifications were from IMDb, where possible.

When referring to “all films” I mean all feature film which grossed at least $1 in the North American theatrical market (i.e. “Domestically”). This means it excludes non-theatrical titles (i.e. straight to video) and also theatrical titles without a reported gross (i.e. The Irishman, et al). “Studio movies” are defined as feature films released by one of the big five/six Hollywood studios, and “independent movies” meaning all other films.

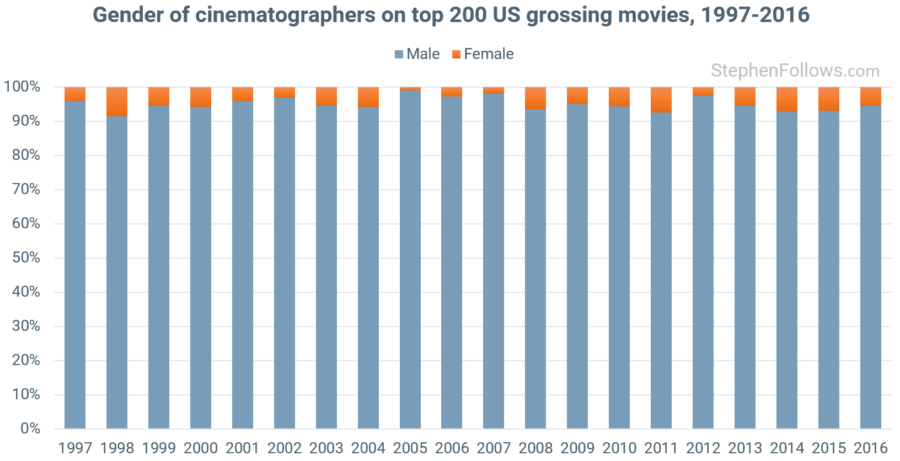

The camera and electrical department includes grips but not Directors of Photography. I studied the gender of DOPs a couple of years ago when I found that over the past twenty years just 4% were female.

To determine a person’s gender, I used publicly available data, pronouns (such as in biographies) and first name analysis (i.e. if 99% of people called Daniel are male then I have regarded every Daniel with an unknown gender as male). I appreciate that this research takes no account of gender fluidity or other forms of self-identification. That’s not a conscious choice but rather a consequence of doing research at this scale. If anyone can suggest a way of taking this on board in the research process then I am very keen to hear it. Please drop me a line and we can talk it through.

If there was anyone for whom I could not reliably determine a gender, then they were not included in the charts which show a percentage split between male and female crew members. Although this is not ideal, I have no reason to think that these people skew towards one gender over another, and they were also a small percentage of my overall dataset. For the vast majority of the period I studied, people are extremely likely to have publicly identified in a binary manner, no matter their true feelings or identity. This research speaks to how people are judged from the outside and it’s the public-facing gender identity that matters most when it comes to discrimination.

Epilogue

I was disappointed to have my figures misreported in The Hollywood Reporter. It may seem like a small error but it matters on a few fronts:

Firstly, the figures are wrong and accuracy is important.

Secondly, they paint a rosier picture than is the case. Across almost all of the gender research I’ve conducted over the years, you can sum up the trend as “The bigger the production, the fewer women you’ll find working on it”. Earlier in this piece, I’ve shown the difference in action.

Finally, the biggest danger the gender equality movement will face in the coming years is the notion that it’s all ‘in-hand’ and nothing more is needed. It took a lot of work from many hard-campaigning folk to get the industry to even take note and the battle is now to effect actual change. The vast majority of people who work in the film industry do not regard themselves as sexist and would be appalled if they discovered that their actions favoured one gender over another. However, when acting as an industry, and with unconscious complicity, the industry consistently takes actions that result in women having a harder time than men.

If you mix this cognitive dissonance over inequality with a few ‘good news’ stories then there is a temptation for many people to think that it’s all been sorted. This breeds complacency and suppresses support for future efforts to level the playing field.

I have contacted The Hollywood Reporter and expect to see a correction in the online edition.