Between filmmakers and film audiences lie a complex network of middlemen, distributors and sub-distributors. They play a vital role in the film value chain, ensuring that films are available all over the world in all manner of formats to all types of audiences.

Between filmmakers and film audiences lie a complex network of middlemen, distributors and sub-distributors. They play a vital role in the film value chain, ensuring that films are available all over the world in all manner of formats to all types of audiences.

This side of the industry is less visible than most other aspects, for a number of reasons. Firstly, they don’t interact directly with the public the way cinemas do. Secondly, their work is not visually interesting. Film fans enjoy behind-the-scenes footage from movie shoots but I doubt behind the scenes of a negotiating re-licensing deal would have the same appeal. Finally, it’s a fairly small sector with a relatively low number of people working in it (certainly compared to the huge numbers of people involved with making a movie).

These reasons mean that despite the huge influence the sector has on what movies audiences are offered, it’s not very well studied. There have been no end of gender and diversity studies within the filmmaking and acting realms, but very little talk about the sales and distribution sectors. So I thought I would take a look and see what we can discover about the people who control what we watch.

I built a dataset of everyone who had attended one of the three major annual film markets in the past ten years (48,845 people in total). I focused on gender diversity, in large part because it’s not possible to determine other aspects (such as race, class or sexual orientation).

A quick primer in the business of international film sales

In order to understand these stats, some readers may appreciate a reminder of how the film value chain works. This is obviously a gross simplification but hopefully should be enough to allow everyone to follow the research. If you’re already up to speed with the sector then you can skip this section.

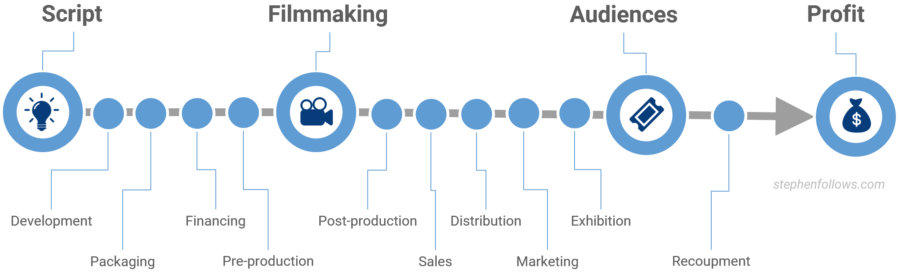

If we were to quiz the average person on the street about how films are made then they would likely be able to pick out four key milestones in a film’s creation – there’s a script, there’s filming, it’s shown to audiences and the money goes back to the people involved. Between each of these key milestones are a myriad of different process and procedures. Below is a simplified illustration of the key ones.

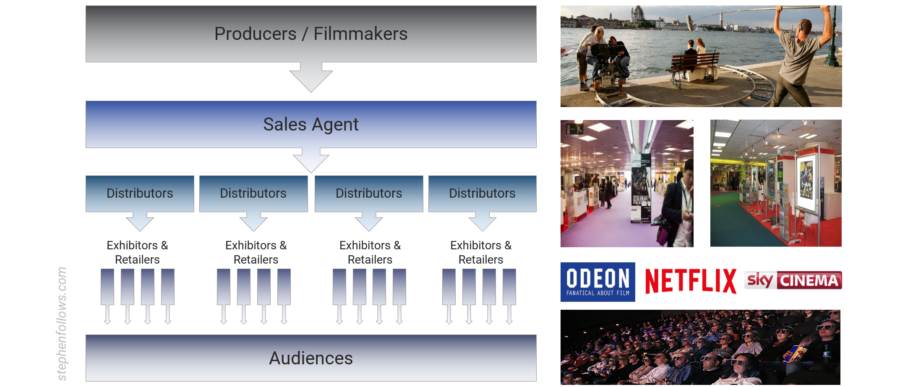

Today’s research looks at the link between the Sales and Distribution stages. In the vast majority of cases, it works like this:

- Each film will sign a deal with one single Sales Agent. This is a company (or person) who will manage the worldwide rights for that movie and only they will be empowered to negotiate and sign deals for that movie.

- They will attend Film Markets and pitch their new movie acquisitions to distributors. These markets are industry tradeshows and each sales agent will have a booth or office where they show off the movies they represent. The three major film markets are the European Film Market in Berlin (held in February), the Marché du Film in Cannes (May) and the American Film Market in Santa Monica (November).

- At each market, the sales agents are hoping to sign a deal with one Distributor from each territory around the world. One territory is normally a single country but sometimes they incorporate a few countries, such as ‘the UK and Ireland’, or ‘Benelux’, which includes Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. If the sales agent signs a deal with a French distributor, then that distributor will have the exclusive rights to distribute the film throughout France.

- After signing deals for new movies, the distributors go back to their home countries and plan the movie’s release. They are the people who pay for the movie advertising you see on buses, on TV, in print etc. They are also the people who supply the film to Exhibitors (i.e. cinemas), TV stations, VOD platforms, etc.

The chart below is an illustration of what the chain would look like if the movie in question sold to just four territories.

If you want to see how money flows back up this chain, you may enjoy my article from last year entitled ‘How is a cinema’s box office income distributed?‘

So, now that we know about the sector, we can start looking at what types of people are attending these film markets and influencing the movies that reach audiences.

How well are women represented at major film markets?

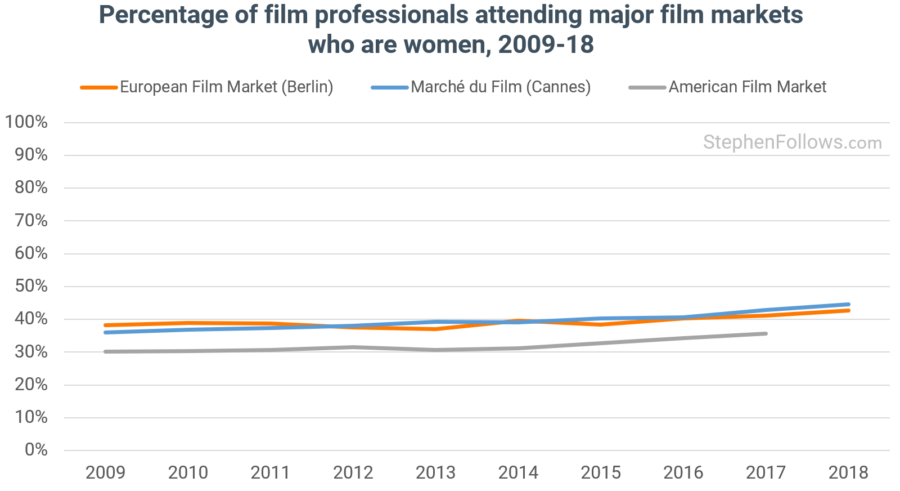

Ten years ago, women accounted for 35% of people attending major film markets, whereas so far in 2018 the figure has risen to 44%.

On the face of it, this is encouraging. It shows that we are getting close to equal representation and the trend is upward (albeit slowly). However, the devil is in the detail.

Taking account of status

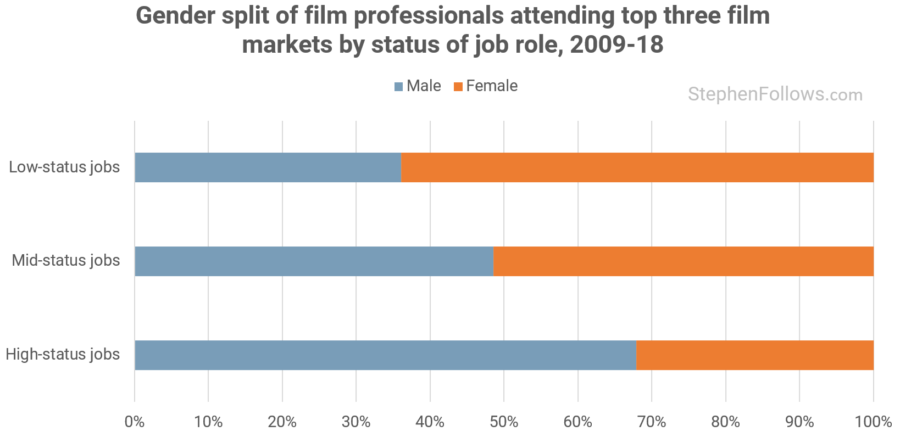

If we divide the jobs people do into three basic categories – high-status, mid-status and low-status – then we start to see a much more worrying trend. (NB: You can read more about my methodology and criteria for these job status designations in the Notes section at the end of the article).

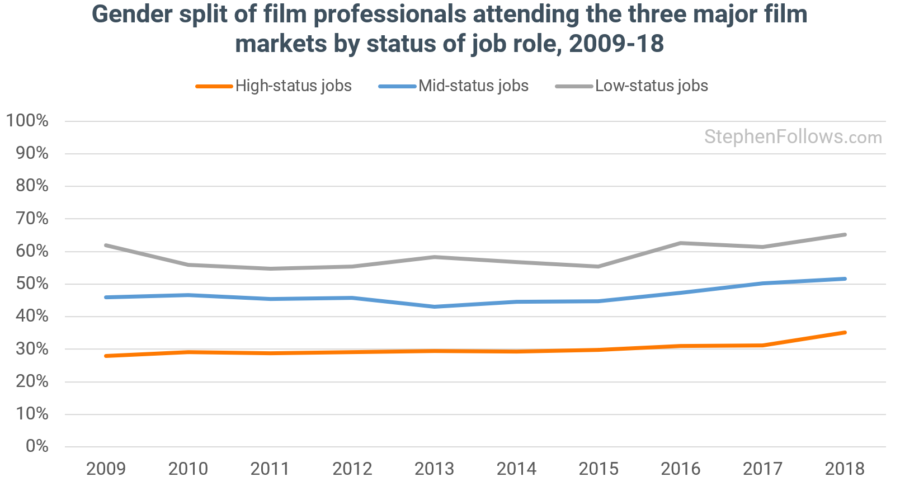

Women account for 32% of high-status employees, 51% of mid-status employees and 64% of low-status employees.

You might assume this means that in a few years time, those low and mid-status employees will work their way up to senior levels. Sadly, the data does not suggest that this will solve the gender imbalance any time soon.

Ten years ago, 28% of high-status roles in sales and distribution were taken by women, and so far this year it’s only moved up to 35%. At this speed, it will take until around the year 2040 to reach parity.

Note: The little uptick you see in 2018 may at first seem a positive change but sadly it’s just a result of the fact the AFM hasn’t taken place yet this year and, as shown in the previous section, the AFM has lower female representation than the EFM and Cannes. So once the 2018 AFM takes place and I add it to these figures, the uptick is likely to mostly disappear.

The most important people at film markets – The Buyers

The highest status someone can have within a distribution company is that of ‘Buyer‘. This is an official designation, verified by the market and denotes that the person in question is a key decision-maker for a company which has successfully bought and professionally distributed movies in the past few years.

This special designation will afford the bearer all manner of extra perks at the market, such as first access to screenings, no need to queue with everyone else, access to dedicated areas and generally better treatment from sales agents and market officials. These Buyers are the key people and the whole reason the markets exist.

The gender inequity is visible among buyers. At the 2018 Cannes Marché du Film, only 36% of buyers were women.

Gender diversity by sub-sector of the film industry

Let’s take a look at how the gender stats look when we break them down by which sub-sector of the industry the companies operate in.

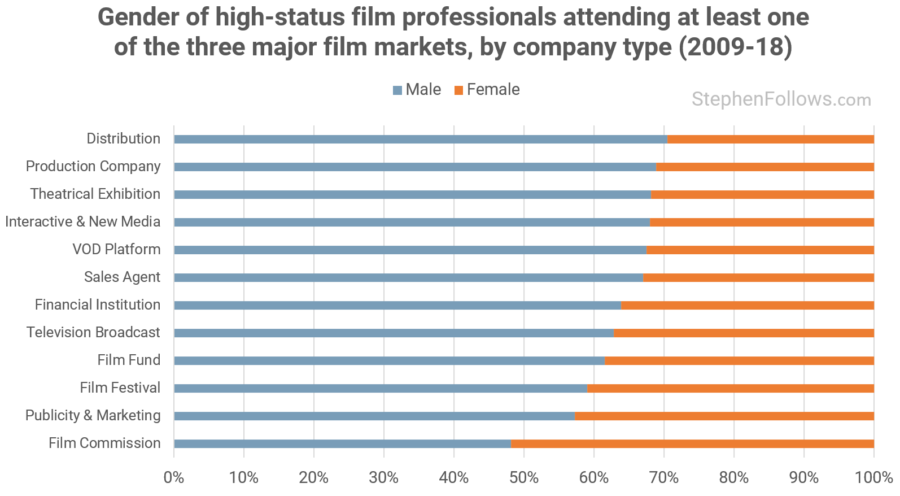

Distribution companies and production companies have the highest percentage of men in high-status jobs (71% and 69% respectively). Only film commissions have a majority of women in such roles (52%), far in front of the publicity sector (43%) and film festivals (41%).

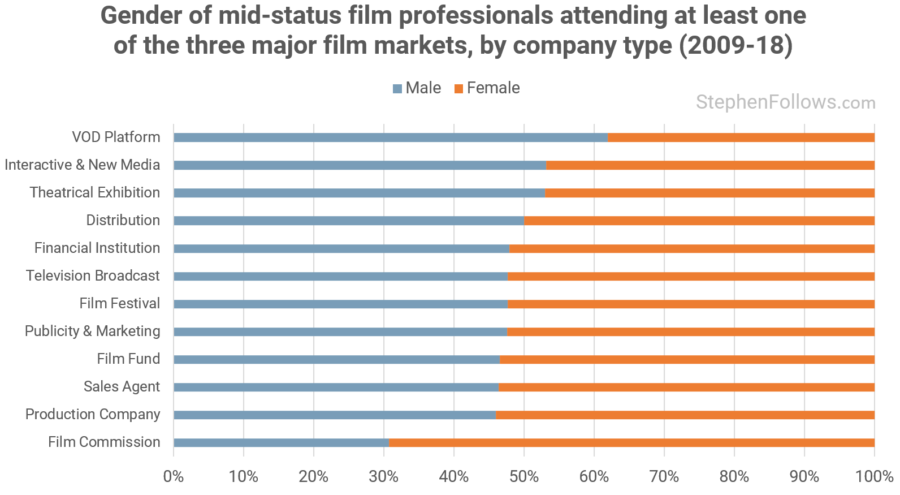

The effect is very similar for mid-status jobs.

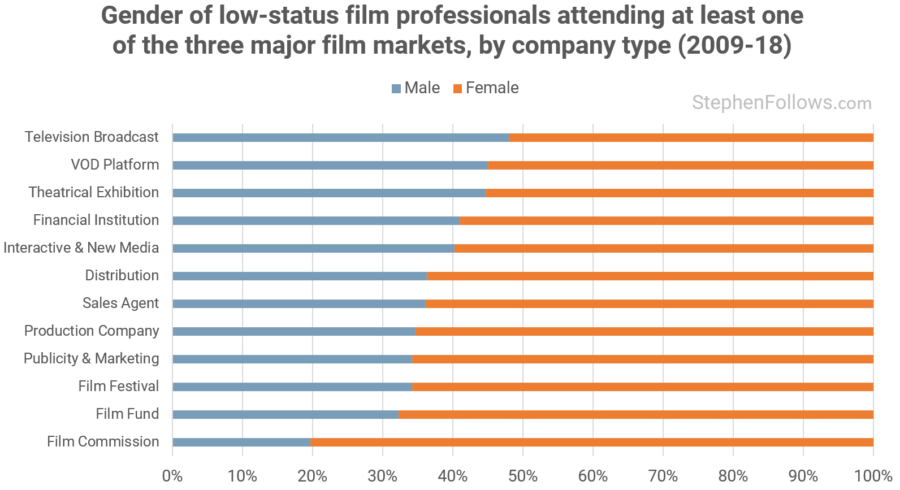

Over four-fifths of low-status employees of film commissions who attend film markets are women. In fact, all sub-sectors have a majority of women in their lowest ranks.

How does this differ by country of origin?

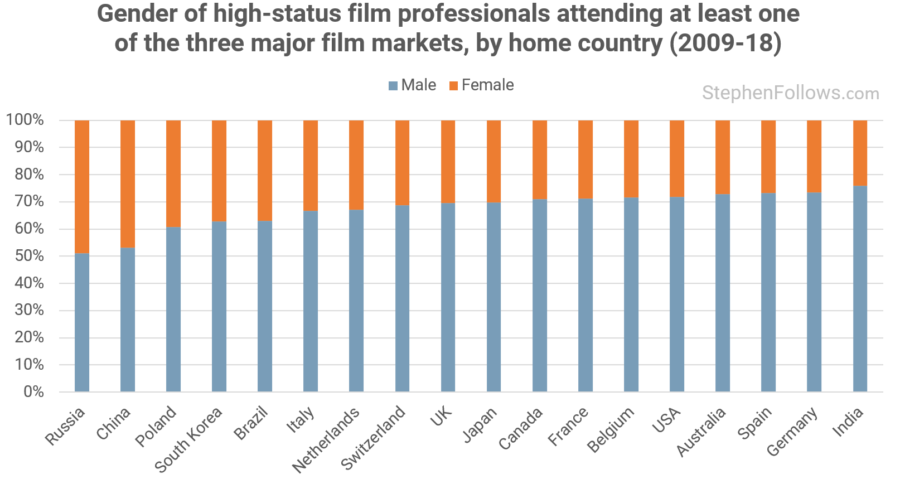

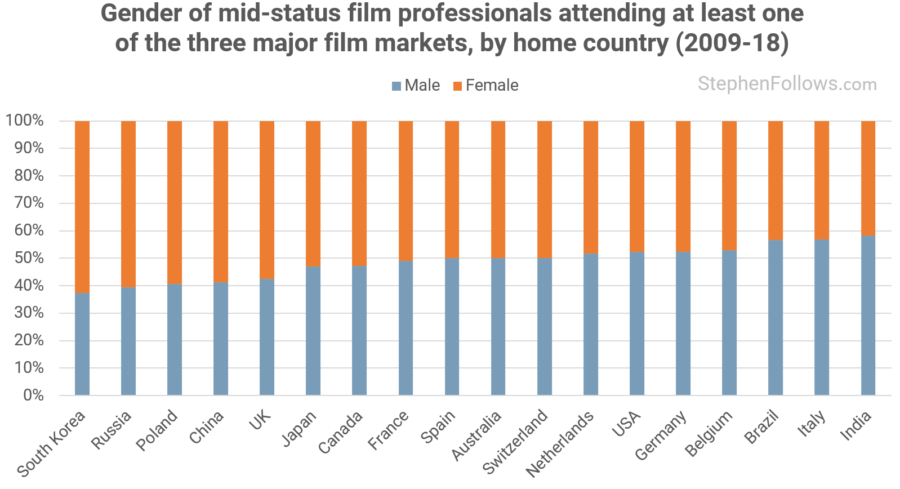

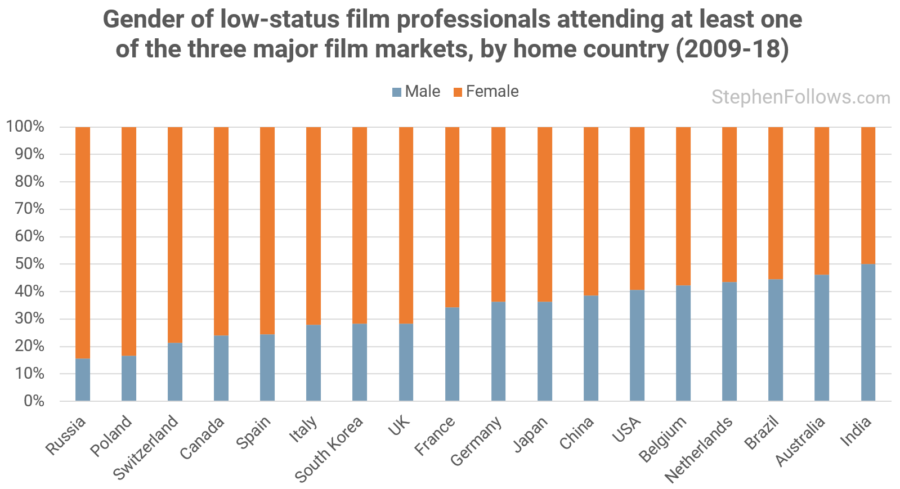

The last lens through which we can view the data is country of origin (i.e. where the person’s normal office is located). The charts below focus on the top 18 countries, as determined by the volume of market participants. All of these countries sent at least 500 people to the three major markets over the decade I studied.

The Russian and Chinese film sales industries have an almost equal number of men and women in high-status jobs (49% and 47% were women, respectively) while Germany and India sit at the opposite end of the spectrum (27% and 24%).

As we have seen previously, mid-status jobs are closer to parity, with South Korea employing the highest percentage of women (63%) and India the lowest (42%).

In low-status jobs, Russia remains the ‘most female’ (a whopping 85% of low-status Russian film sales professionals were women) and India remains the most male (50% were women).

Why does this matter?

I wanted to end on a brief note addressing why gender diversity in sales and distribution matters. To me, the two biggest reasons are:

- Fairness. Unless we believe that women just don’t want senior roles or are inherently bad at them (neither of which has ever been shown) then the logical conclusion is that there is an inequity of opportunity. This is patently unfair to women and should have no place in a modern society.

- The effect on film availability. The sales and distribution sectors are relatively small but wield a lot of power over what movie audiences are able to choose to watch. While it seems unlikely that many people are consciously choosing to ignore possible profitable films from and about women, it does appear that the unconscious bias which has been proven in other elements of the film industry is at play here too. Audiences deserve to have a diversity of stories to pick from, not just those which male buyers chose to support.

If you’re interested in reading more about the topics in today’s research, then you may enjoy some of these articles on film markets:

- Cannes film festival mysteries explained (via Nicolas Cage)

- How much does it cost to exhibit at the Cannes Marché?

- How big is the European Film Market?

- How many people attend the American Film Market?

Or these on gender diversity:

- A major new study into gender inequality in the UK film industry

- UK films with public funding hire more women

- What percentage of a film crew is female?

- What percentage of a UK film crew is female?

Notes

This dataset is made up of people who have been listed as film professionals who attended any of the following film markets: European Film Market (2009-18), Marché du Film (2009-18) or the American Film Market (2009-2017). This does not include delegates exclusively attending the festival components of Cannes or Berlin unless they also attended one of the other markets. In short, if they paid for a professional market pass then they would be included, but not if they were accredited for free at a festival.

The principal sources were Cinando and the official market guides while secondary information came from company websites, Google images and Microsoft’s Azure’s facial recognition engine.

Of the people in my dataset, around 60% stated their job role publicly. Job roles will change over time and so I have opted for the most recent job title they used at the last market they attended. In many cases, someone with a high-status job today would have previously held mid- and low-status jobs (such as someone who moved up the ranks of a company) while in other cases people may jump straight into high-status jobs (such as people who form their own company and so first appear as a CEO). The classification of statuses is subjective. I tried to apply the same judgements and rules to all jobs when classifying, so at least there should be consistency to my subjectivity. I classified jobs before I determined participants’ gender in order to avoid either conscious or unconscious bias in the classification process.

- High-status jobs include CEOs, company directors, managing directors, etc.

- Mid-status jobs include heads of department, managers, vice presidents, etc.

- Low-status jobs include interns, assistants, coordinators, etc

Gender was determined by pronoun use in biographies, first names (for names with an extremely high level of gender certainty) and facial recognition via Microsoft’s Azure API. In real life, not everybody’s gender is binary and I appreciate that classifying it as such is slightly reductive. I don’t have a way to account for gender fluidity as such at such a large scale of research. If anyone can suggest any methods for doing so then I am keen to learn more.

The country of origin data relates to where the person’s office is based, not their nationality nor race. Therefore, a French woman who lives and works in Moscow for a Russian distributor would show up as Russian. This is not a major concern as (a) the majority of people working in a country are also citizens of that country and (b) we’re focusing on the cultural differences of national film industries, not looking for effects based in ethnic or racial origin.

Epilogue

I am a board member of Birds’ Eye View, an industry organisation which aims to spotlight, celebrate and advocate films created by women, and support women working in the film industry. It was at a recent meeting that the topic of women in international sales came up and it sparked the idea to study this topic.

Comments

Thanks for this powerfully simple and eye-opening analysis. You’re right that the sales and distribution sector is one of the most invisible despite its importance. It would be great to see more research in this area!

No problem. I am investigating ways to make it more transparent. Hopefully there will be more here soon…

Olá, eu queria saber se vocês que tem conhecimento com cinema, para trabalhar fora do Brasil é preciso faculdade ou um curso de cinema e audiovisual é necessário? muitos falam que a faculdade cobre mais a parte teorica mas não a prática e cursos como do hollywood film academy são melhores mas duram apenas um ano. Para arrumar trabalho fora do Brasil é possível apenas com um curso de cinema de um ano?

Obrigado por sua pergunta. Me desculpe, mas eu não posso responder, pois não é um tópico que eu sei muito sobre. Boa sorte!