In the past few months, I have received a growing number of questions relating to international collaboration on movies. Some relate to the individual level of cast and crew working across borders while others focus on films as commercial products manufactured in more than one country.

In the past few months, I have received a growing number of questions relating to international collaboration on movies. Some relate to the individual level of cast and crew working across borders while others focus on films as commercial products manufactured in more than one country.

It’s hard to tell why the topic of international collaboration in the film industry is becoming more frequent in readers’ questions. It could be Brexit specifically or a more general sense that as nationalism rises around the world, the need for partnership in the arts increases.

With no Brexit deal on the horizon, we are still unsure what Britain’s departure from the EU will mean for the British and European film industries. Some aspects both have previously relied upon will remain in place (such as geographic proximity and the legal structures around official co-productions) while others are under threat (such as the free movement of people and money). I have looked at what Brexit could mean for the film industry in more detail here, here and here.

Today’s research is a look at how interdependent the film industries of two countries can be, and which countries collaborate most frequently.

I started with my dataset of all 160,618 movies made worldwide between 1990 and 2018 and looked at their countries of origin. There are more details about my methodology and dataset in the Notes section at the end of this article.

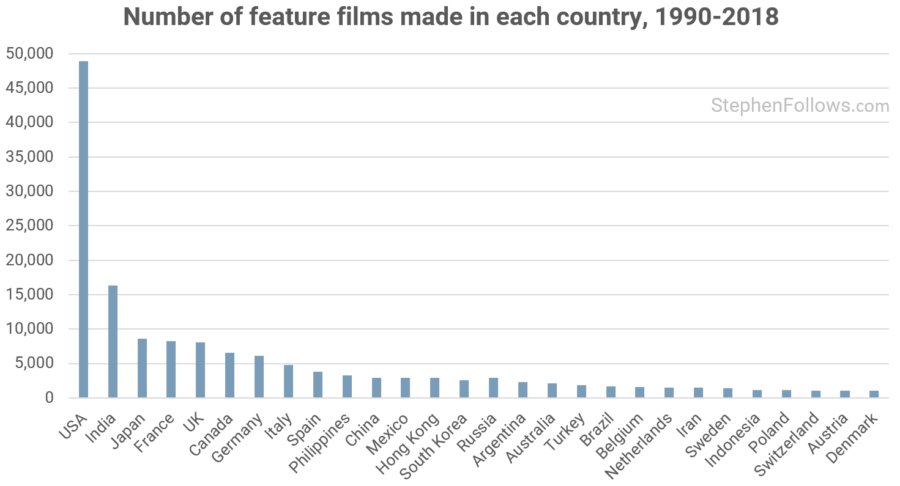

Which countries produce the greatest number of movies?

Let’s start our journey by understanding which countries have the largest volume of film production.

More movies are made in America than in any other country. So much so that they account for more movies than the next five biggest producers combined.

How many films come from more than one country?

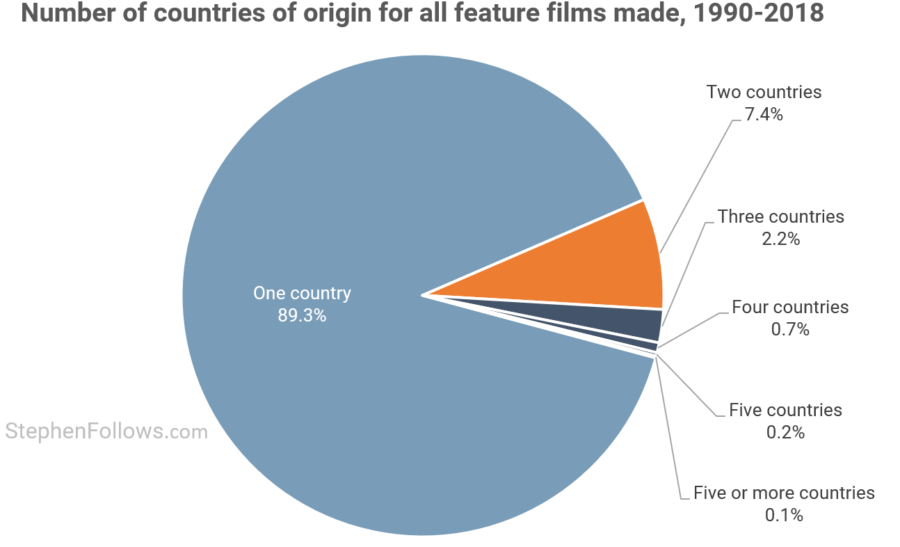

Next, we need to consider that movies can be made in more than one country. Sometimes this is as light as the crew shooting scenes in multiple countries while other times it can be a major part of the financial and production plan.

The latter model is often structured as ‘Official co-productions’ and relies on treaties agreed between the national governments. If a film qualifies as an official co-production then it may be possible to benefit from tax breaks and preferential treatment from each of the countries involved. So a film could be both officially French and officially British at the same time.

Making a film in more than one country requires one or both of the following forms of international collaboration:

- Official co-productions require national governments of each country to negotiate and sign a co-production treaty. Some are long-standing while others are much newer; the UK signed an agreement covering most European Nations in 1992, but only agreed to a treaty with Brazil in 2017. You can read more about the UK’s co-production treaties and process here. There may be restrictions on the cast and crew or requirements in order for films to qualify, such as the American/Chinese agreement which requires that at least a third of the cast be Chinese.

- Even if a film is not using an official co-production structure (either because their two countries don’t have a treaty in place or the producers judge it not to be worth the extra work), the producers and filmmakers from each country will need to work together. This will involve communicating, agreeing on a structure and collaborating together during each stage of production. Each film can be set up differently, so there is no fixed template for cooperation. In many cases, producers from each country will work to secure funding for the production, with their power linked to their level of financing.

Given the complexity and cost of working with partners in another country, it is perhaps not surprising that almost nine out of every ten films made worldwide were produced in just one country. 7% of films were produced in two countries and a further 3% were produced in three or more countries.

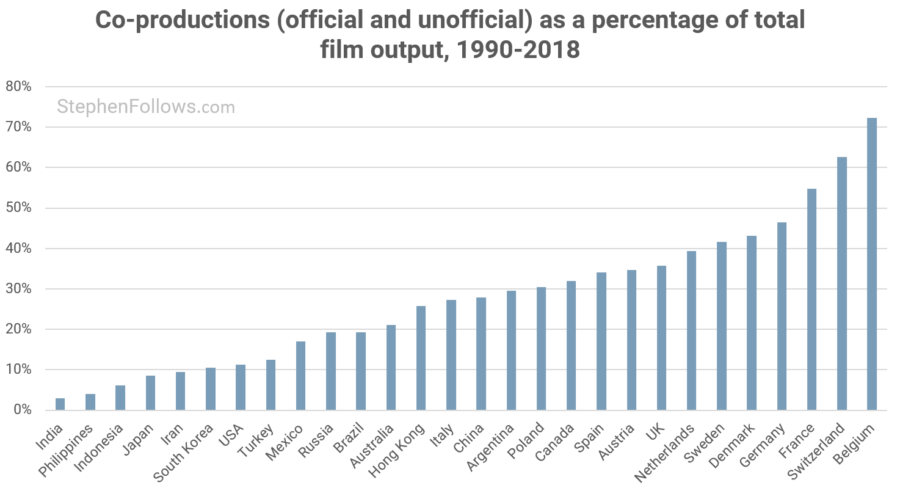

Which film producing nations are co-production junkies?

There will be many factors which affect whether a nation’s filmmakers are likely to team up with those of another nation. These include:

- A shared language.

- A shared culture.

- A shared approach to making movies.

- The logistics of moving money, people and equipment across borders.

- If there are tax breaks or other benefits on offer.

- The locations, services and people available in each country.

These mean that some nations are much more likely to create co-productions than others. Of the top film producing nations, Belgium has the highest rates of co-productions, with 72% of their films also being from another nation. The top ten countries on the chart below are all European nations (at least at the time of writing).

The countries with the lowest levels of co-productions include India (3%), the Philippines (4%) and Indonesia (6%).

Spotting common co-production bedfellows

Now that we’ve identified which of the films made over the past three decades were produced in more than one country, we can start looking for ‘common bedfellows’. These are countries whose filmmakers most often team up to make movies together.

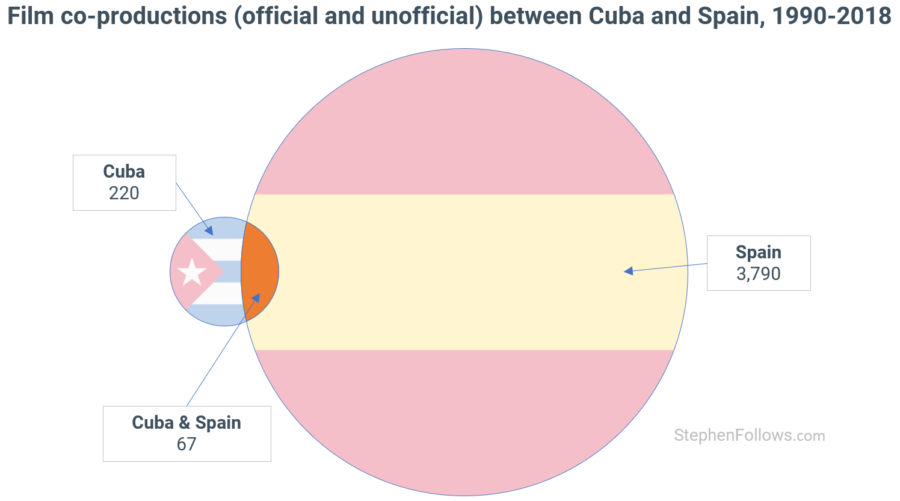

Just before we look at the top bedfellows, it’s worth quickly considering the asymmetric nature of international collaboration. For example, over the period I studied, 220 movies were produced in Cuba, 3,790 in Spain and within those were 67 Cuban-Spanish productions. That means that almost a third of all Cuban films were also Spanish productions, but that fewer than 2% of Spanish productions were Cuban.

Therefore, if we were to ask “Are there a significant number of Cuban-Spanish co-productions?” we would need to know who’s asking. From Cuba’s perspective, Spain is an important co-producing partner, whereas from the Spanish perspective, Cuban co-productions make up a tiny percentage of Spanish films.

The list below shows the top co-producing bedfellows across the top 67 film-producing nations (i.e. those with at least 200 movies during the 29 years I studied):

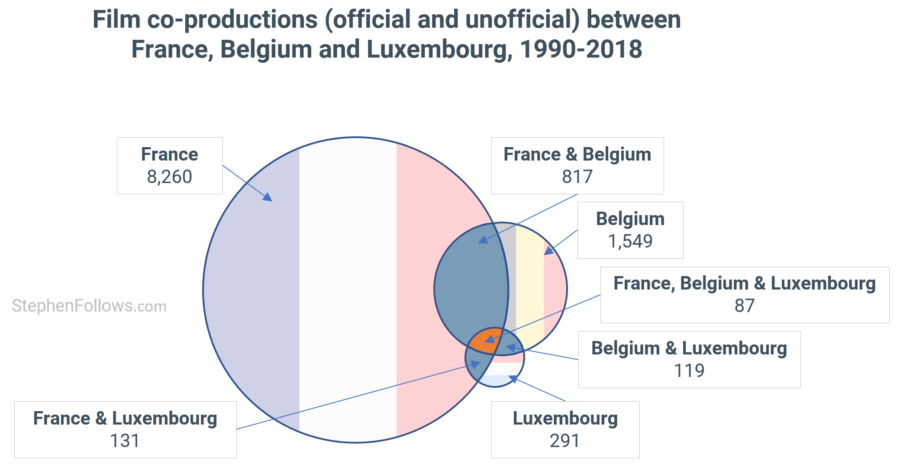

- 53% of films from Belgium were co-productions with France

- 45% of films from Luxembourg were co-productions with France

- 41% of films from Luxembourg were co-productions with Belgium

- 38% of films from Slovakia were co-productions with Czech Republic

- 31% of films from Switzerland were co-productions with France

- 30% of films from Cuba were co-productions with Spain

- 27% of films from Portugal were co-productions with France

- 26% of films from Ireland were co-productions with UK

- 24% of films from Morocco were co-productions with France

- 23% of films from Denmark were co-productions with Sweden

- 22% of films from Luxembourg were co-productions with Germany

- 21% of films from Luxembourg were co-productions with UK

- 21% of films from Austria were co-productions with Germany

- 21% of films from Switzerland were co-productions with Germany

- 20% of films from Norway were co-productions with Sweden

- 19% of films from Canada were co-productions with USA

- 19% of films from Ukraine were co-productions with Russia

- 18% of films from Taiwan were co-productions with Hong Kong

- 17% of films from Sweden were co-productions with Denmark

- 17% of films from Romania were co-productions with France

As you may have spotted, Belgium, France and Luxembourg feature in the top three. To help you visualise that better, see below for a Venn diagram of their co-productions over the past three decades.

How will Brexit affect film co-productions?

As a final thought, I thought it might be useful to look at how Brexit could affect UK co-productions. For the past two years, only one thing has been certain about Brexit: when it would happen. Given that now even that is changing, we know less than we ever have before about what Brexit will look like and how it will affect the film industry, both in the UK and abroad.

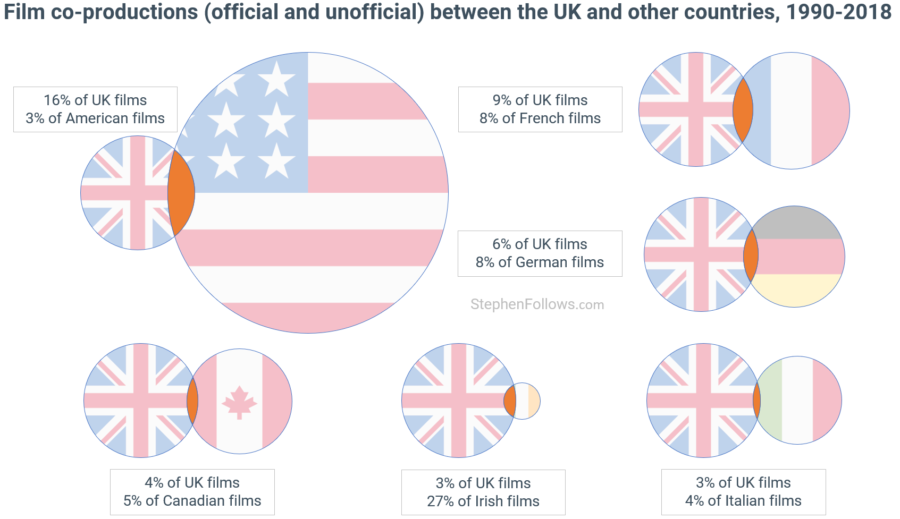

To prepare us to evaluate whatever comes of the Brexit talks, here are the top six (from the UK’s perspective) co-producing nations for UK films.

UK-American co-productions account for 16% of UK films but only 3% of American films. Conversely, UK-Irish productions are just 3% of UK films and 27% of Irish films.

Further reading

If you’ve enjoyed today’s research then you may also enjoy the following articles:

- How the genre of film production changes around the world

- Genre trends in global film production

- The big changes taking place in UK film production

- The effect of Brexit on the UK film industry

- How will Brexit affect the UK film industry?

- What does a post-Brexit UK film industry look like?

Notes

The data for today’s research came from a number of places, principally IMDb, The Numbers, Wikipedia, Box Office Mojo and OMDb. My dataset is of all fiction feature films made and listed on those sites. Genre classifications were from IMDb, where possible. The years refer to their first public release date, not when the films were shot.

What qualifies as a feature film can be a complicated subject, and is only getting more so with the rise of made-for-streaming feature-length productions, feature-length episodic television content and non-traditional distribution methods. It’s possible that the sources I used to build my dataset have a Western bias (both because of their language and their business focus). From previous research, I don’t think this is a significant factor in today’s research but I wanted to mention it, as it often comes up when discussing the most voluminous film production nations (for example, Nollywood, which arguably does not create traditional feature films).

When looking at the bedfellows list, I narrowed my search to the 67 countries which had produced at least 200 movies between 1990 and 2018, to remove outliers with low production volumes.

Over time, countries emerge, change and disappear. For example, at the start of the period I studied, the Soviet Union was (just about) standing, Yugoslavia was yet to split, Germany was split and Hong Kong was a British Dependent Territory. Without wanting to minimise such changes in a geopolitical sense, they did not have a great amount of effect on today’s research. I included the pre-1991 Soviet films within Russia. Yugoslavia and its resulting countries are not large producers of movies, I combined East and West Germany and Hong Kong is still counted as a separate territory for the purposes of tracking movies. I appreciate that these are simplifications of complex political situations but they were done in the pursuit of clarity and brevity.