Yesterday a strike among crew members of US TV and film productions was called off, barely a day before it was meant to start.

IATSE (or to give it its full name The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States, Its Territories and Canada) was holding out for better pay and working conditions for its members, who span numerous departments on film sets.

Only time will tell if this deal will be ratified by the membership, but at the time of writing things at least the imminent threat of a crippling strike has abated.

Last week I received a number of questions from readers related to the data behind crew of US productions. IATSE has a slightly complicated set-up involving many different job roles, membership criteria and a network of many local chapters (a few of which has already agreed their own deal so would not have been out on strike). This makes it tricky to give hard numbers on the likely number of possible strikers or affected productions.

However, I can help by giving a rundown of the number of people involved with productions more generally, how it’s differed over time and by the size of production, and which are the largest departments. To do this I built a dataset of all theatrically released live-action movies released in the US between 2000 and 2019 and studied the number of crew credits.

How many people work on a film?

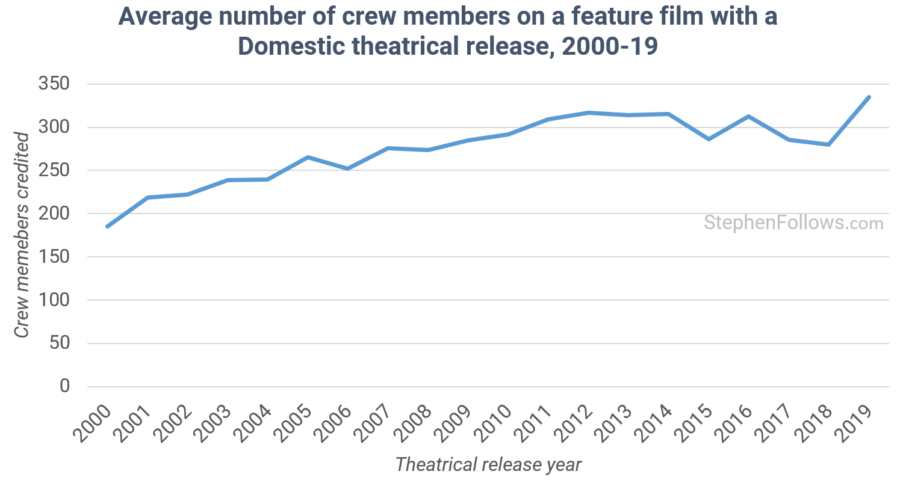

Between 2000 and 2019, the average film released in North American cinemas employed 276 people in crew roles. This covers development, pre-production, shooting and post-production.

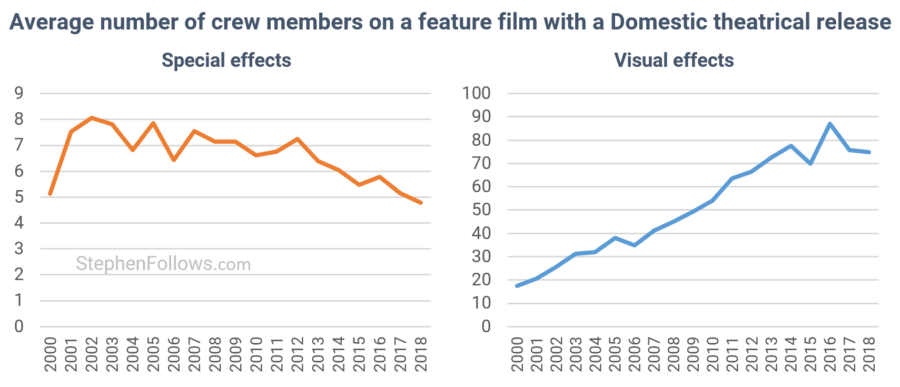

Over the past two decades, the number of crew members on a film has increased by 51%, from 185 in 2000 to 335 in 2019. However, this change has not been uniform. Perhaps the starkest change has been in the different trends between Special Effects jobs (i.e. physical effects such as rain, wind, and explosions) and Visual Effects jobs (computer-based effects).

How wide is the range of employment numbers?

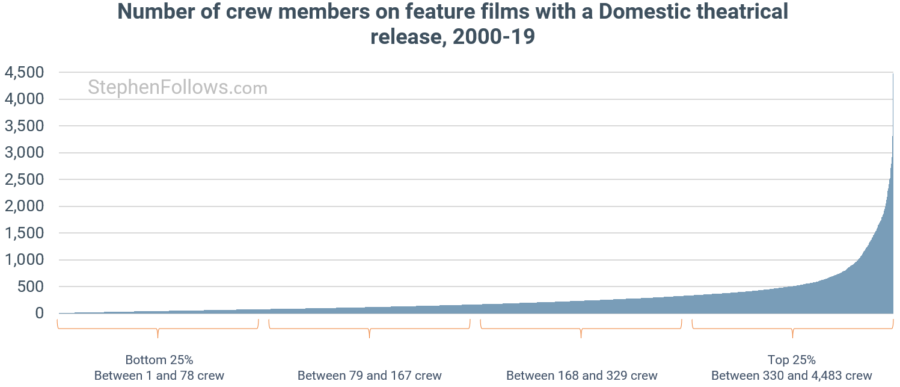

A common theme in film data analysis is power laws. A small percentage of movies make most of the money, a small number of people hold most of the power, etc. In this case, it means that a small number of big productions disproportionately employ a large number of people.

The chart below shows all the 8,095 films I studied, sorted by the number of crew members who worked on them. Half of all productions credited fewer than 168 people, but just 92 productions (i.e. 1.1% of all movies produced) provided 10% of credits.

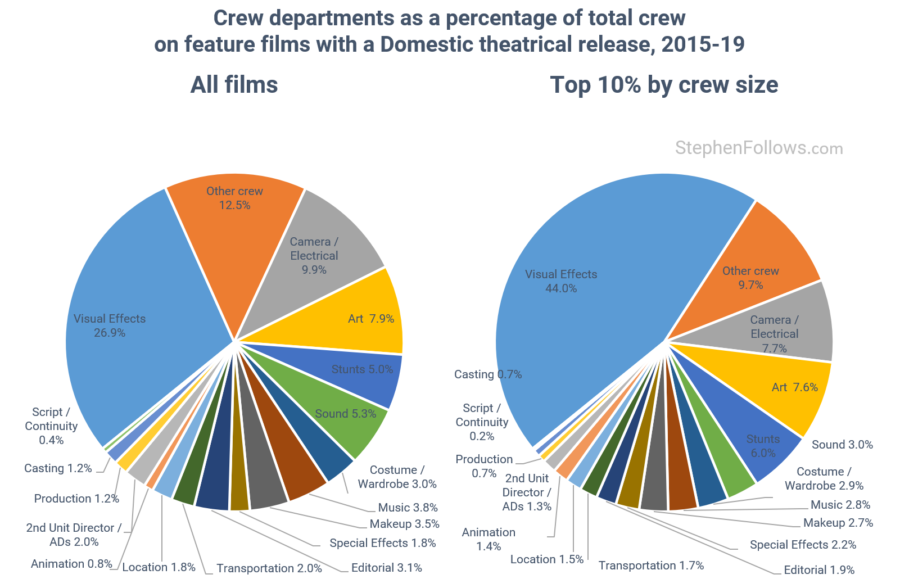

When a movie doubles in size, not all departments are doubled. For example, the number of directors is unlikely to change. To show this change visually, the two pie charts below show how crew members are split between departments, on all movies (left) and just on the top 10% largest productions, by crew size (right).

We’ve already seen how Visual Effects departments have been growing over time, and this is also the case for the very largest productions (more on that here).

Which films employed the most people?

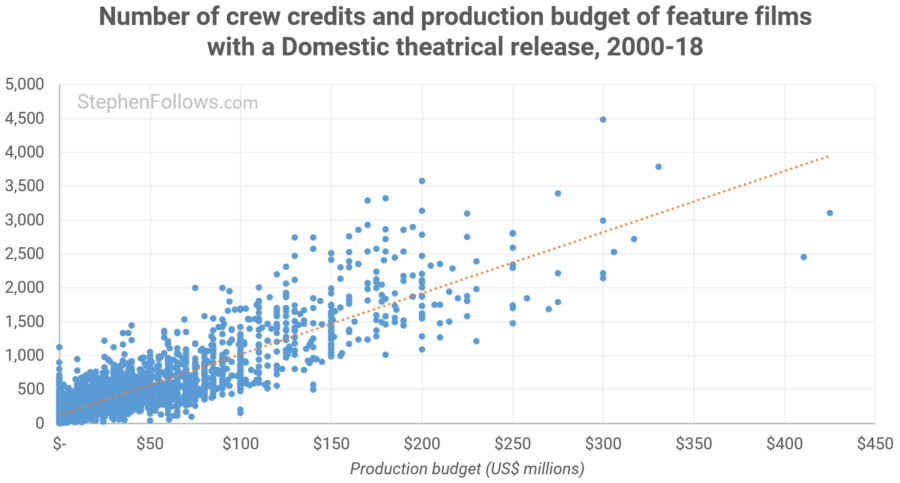

Overall, the number of crew members credited on a movie is strongly linked to the film’s budget, with a Pearson correlation of 0.89 (where zero means no correlation and one means a perfect correlation).

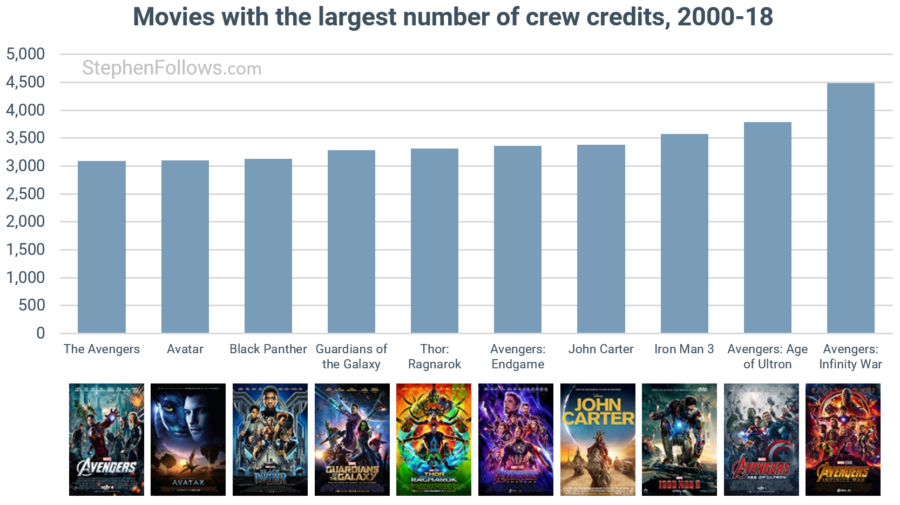

The movies with the greatest number of crew credits were Marvel movies, with the studio accounting for eight out of the ten top films. In fact, 4.3% of all movie credits between 2007 and 2018 were on films produced by Marvel Studios.

Further reading

If you’ve enjoyed this article then you may enjoy these related pieces:

- Which film departments are the most isolated?

- How has the average Hollywood movie crew changed?

- Do more film crew members work on-set or in post-production?

- How many screenwriters does it take to write a movie?

- How many stunt performers work on a movie?

- How many Assistant Directors work on UK and US movies?

- How many editors does it take to edit a movie?

- What is happening to Second Unit Directors?

- How many films does the average director make?

- On average, how many films does a producer produce?

Notes

Today’s research is looking at live-action feature films that were released in North American cinemas between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2019. My data for today’s research comes from IMDb, Wikipedia and other public sources. There are a few things to bear in mind with this research:

- The data goes up to 2019 as credits can take time to appear in their entirety online and becuase the pandemic messes with the “theatrically relased” criteria, after cinems were shut for a large part of 2020.

- When referring to “crew” I am not including actors or background artists.

- Meauring credits and tracking indivdual people is not the same thing. One person may work on many films in any one year, espesially if their job is highly specialised and therefore only brought in for a few days work on a produiction. One person working on twenty productions in a year will show up as twenty crew credits in today’s research.

- This tracks people and credits, not hours/days worked. Someone may work just one day on a production while another works for months – each only receiving one credit apiece.

- Movie credits are not always complete, with some sectors like visual effects suffering from caps on the number of people who can receive a credit, no matter how many actually worked on a film. I have studied this topic in detail in the past – How many movies credits go uncredited?

- In recent years, Studios have started adding notes towards the end of movie credits which estimate how many jobs were connected to the film. The first was Taken 2 which included this line in the final credits roller: “The making and legal distribution of this film supported over 14,000 American jobs and involved over 600,000 work hours“. I haven’t used these calculations in today’s research as they fall more into the category of PR than data science. For example, another Fox film that same year, Life of Pi, used the exact same statement and numbers.

Epilogue

My research is looking at direct jobs, by way of movie credits. There are many more people who will support the release of a film who do not receive direct credits, such as those in marketing, distribution and within the corporate structures of the companies involved. Then there are also people whose jobs depend on the people working on films, such as suppliers of raw materials for art departments, manufacturers and hiring houses for equipment, journalists on trade publications, etc, etc.

Therefore these numbers do not show the full extent of the movie business’ impact. In the US, the MPPA says “In the United States alone, the film, television, and streaming industry supports 2.5 million jobs“.

Also, it’s worth remembering that “just” one job may be supporting a whole family. Film jobs are typically uncertain at the best of times and recent events have shown just how hard it can be to be a freelancer.

Comments

If you ever want to watch VFX workers turn quite angry, mention credits to them. Though many releases do, indeed, have a very long roll-call of VFX workers, they also often leave many of them off, with facilities houses being pressured to reduce the number of screen credits given.

Good day, Mr. Stephen.

I have to say, I am thoroughly impressed by your website/blog, and what you’ve managed to compile and quantify. I may be speaking for a small proportion of people out there, but it is truly refreshing to see proper statistical analysis in quite a number of areas in the motion picture field.

I wrote this message to express my admiration and gratitude for your work.

Regards