As we start to ease out of the ‘pandemic emergency’ phase, I’m getting an increasing number of questions about the effects the pandemic had on the film business.

The short answer to almost everything I’m asked is – it’s too early to tell.

When the dust has settled, it’s likely that the changes we’ve experienced in the past three years will fall into one of three categories:

- Long-term trends. Changes which were already taking place and so once the pandemic is over, we should expect them to return to their longer-term trend. One such example is likely to be the increase in the number of films being shot.

- Pandemic-specific short-term trends. These are things which are directly related to the virus, lockdowns, and recovery. One such example would be the shutting of almost all cinemas worldwide. The effect of these things will soon disappear, if they haven’t already.

- Pandemic-accelerated long-term trends. Things which the pandemic affected but which were already in the ether. These could include the increased importance of streaming in the value chain. The pandemic sped up something which was already taking shape.

There are a few topics which I can’t easily place just yet, such as the frequency of cinema-going, and whether film markets will return to being wholly physical affairs or remain hybrid.

The topic for today might be a mix of all three.

There is no doubt that shooting a film during the pandemic was more expensive than it was in the Before Times. Films suddenly needed more time, space, people, and equipment – pretty much the most expensive parts of any production.

The exact impact on the bottom line varies depending on who you ask. Tim Bevan of Working Title called the Covid costs “horrifically expensive“, Variety reported that producers were putting the figure at between 10% to 15%, while a California Film Commission study calculated the additional costs at just 5%.

At the same time as these specific additional costs were introduced, there seems to be a general feeling that films are growing in scale and complexity. But the plural of anecdotes is not data! Let’s crunch the numbers and see what we can discover.

To do this, we have to clear an awkward data hurdle first. Namely, my usual criterion of “All films released in US cinemas each year” became meaningless during the pandemic years. For brevity’s sake, I have moved the long explanation of my new criteria to the end of the article. Data nerds – I’ll see you there.

The important thing to know is that I tracked 4,664 movies which fit my new criteria, released between 2000 and 2021 and for which a budget figure is publicly available.

Has the average movie budget increased?

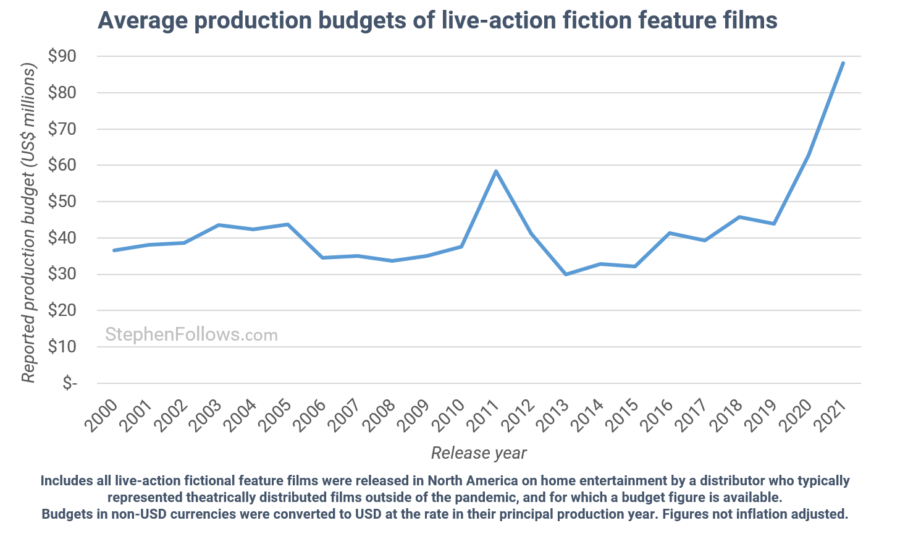

Let’s start with a clear, simple chart and then let me tell you why we should be suspicious of it.

The chart below shows the average budget for all movies in the cohort. In 2000, the average budget was around $38 million. It was roughly flat for a decade, before jumping in 2011 to just over $60 million and then returning to under $40 million a few years later. Then, from around 2015, we start to see a clear and prolonged rise.

By 2021, it has ballooned to $87 million – well over double. These are not inflation-adjusted figures but (a) inflation didn’t rise in this pattern; and (b) even taking that into account, we’re still seeing a roughly 50% rise from 2000.

Ok, let’s put on our critical goggles.

The first thing to note is that this is the average, meaning the total spent divided by the number of films made. This means if the only change were to be a reduction in the number of inexpensive films being shot, then the overall average budget would increase.

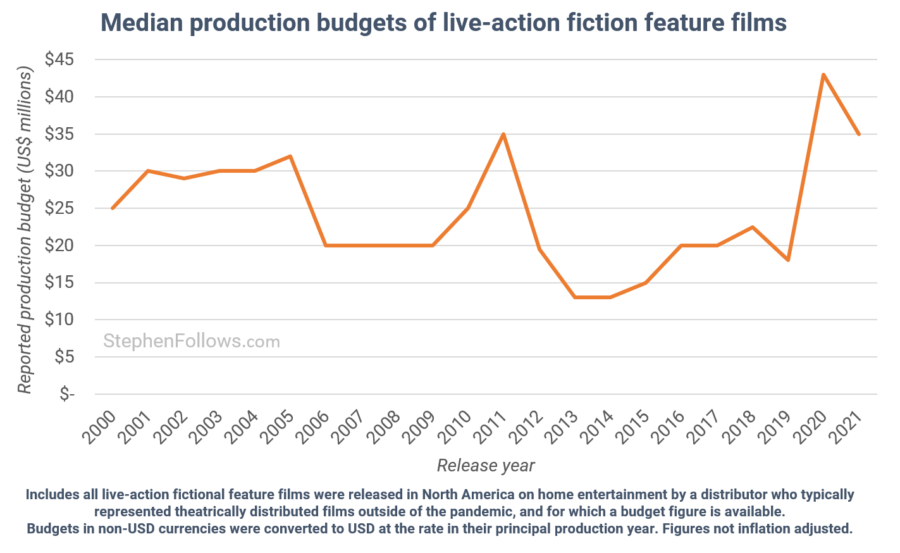

So instead, let’s track the median budget – i.e. the midpoint between all the budgets of each year.

Hmmm still a rise, but a far less dramatic one (note the different scale on the vertical axis). This time the growth in the second decade is from $19.8 million in 2012 to $42.5 million in 2021.

Let’s pull apart the data by budget level.

How does the picture change by the scale of production?

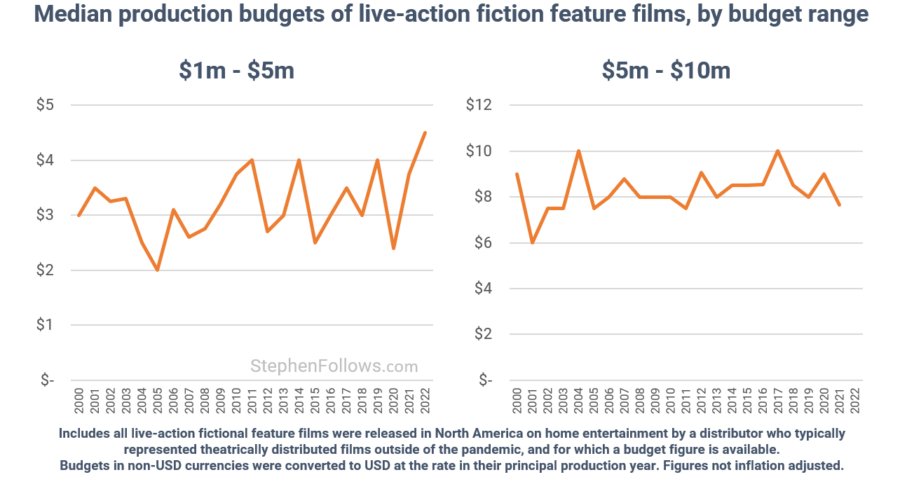

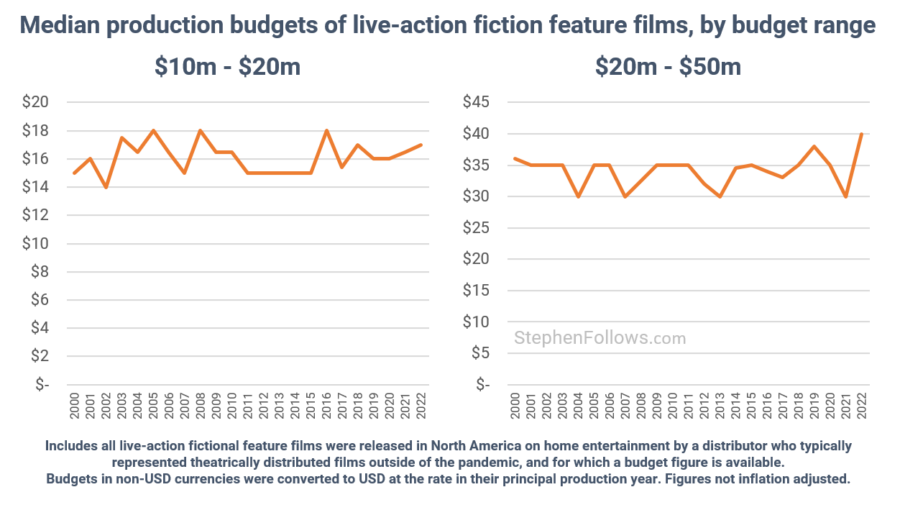

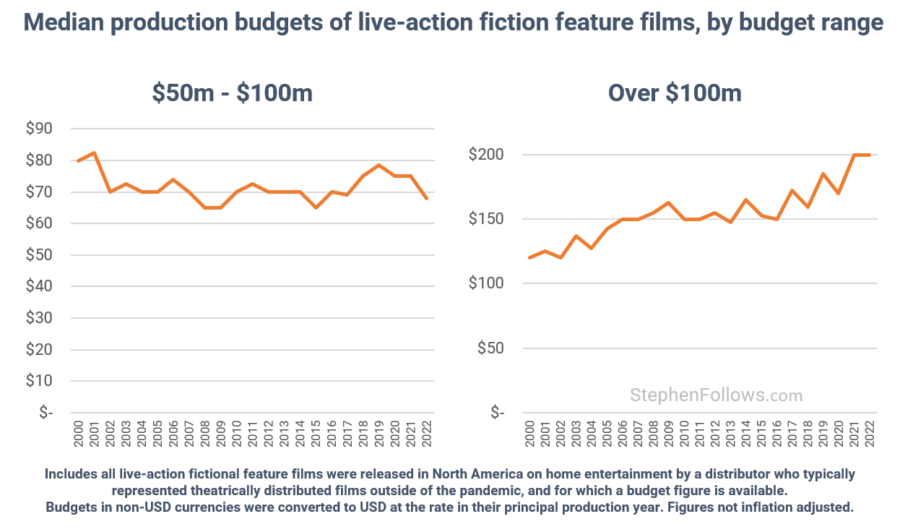

I’ve grouped the films into different budget categories and calculated the median for each.

The smallest films are the ones most likely to have unreliable data (see Notes section for details) so we can’t read too much into the spikey chart on the left. And films costing between $5 million and $10 million don’t reveal a recent rise.

The next couple of budget ranges also show a fairly flat trend in recent years.

Whereas when we turn to the very biggest films, we start to get a better idea of what’s happening. While those costing between $50 million and $100 million don’t show much change, those costing over $100m have seen a dramatic increase.

So we have found our culprit. While there are a load of caveats related to this data, I think it’s safe to say that the rise in median budgets for movies in the past few years has almost exclusively been driven by a rise in the cost of the very biggest films.

These were also the films that were more able to keep shooting during the worst of the pandemic. They had powerful people behind them and they are the backbone of trillion-dollar businesses, which even a global pandemic can’t hold back.

So while most films just delayed their shoot, the biggest films carried on and scaled up their budgets to accommodate the new requirements.

It’ll be fascinating to see what happens in the coming years.

As covid departments are being disbanded and traditional ways of working become the norm again, will we see a reversion to the pre-pandemic cost base?

Or are there other underlying reasons behind the increased price tag, which will live on even when we’re all maskless and fancy-free?

Time. Will. Tell. (i.e. wait for the sequel, folks).

Learn more about movie budgets

If you want to know how a film’s budget is spent, you may enjoy these previous articles, which go into much more detail than I will today:

- How do film budgets change as they grow?

- How movies make money: $100m+ Hollywood blockbusters

- How films make money pt2: $30m-$100m movies

- How much does the average movie cost to make?

- Is a movie’s box office gross connected to its budget?

- Has the mid-budget drama disappeared?

Notes

If you’re a regular reader of this blog then you’ll know that I often use ‘All films released in US cinemas as a neat cohort of movies. It allows us to study both Studio and indie movies, but also weed out the homemade microbudget movies (which while perfectly artistically valid, don’t help our understanding of the business of film).

But, as mentioned above, for over two years, most cinemas were either closed or working to a highly irregular schedule. Most new movies skipped theaters and opened directly on Home Entertainment.

So to be able to have a consistent dataset of movies to study before, during, and after the pandemic, I needed to create a new inclusion criteria. I spoke to a number of people in the film data community and after much pontificating in the end settled on the following slightly clunky, imperfect classification:

All live-action fictional feature films were released in North America on home entertainment by a distributor who typically represented theatrically distributed films outside of the pandemic, and for which a budget figure is available.

I opted to focus on the video distributor as the common denominator, rather than the production company or studio, as I feel it’s more closely linked to a film’s commercial merits than the aspirations of the people who created the project.

The data for today’s research came from the OpusData / The Numbers, IMDb, Wikipedia, Box Office Mojo and the film trade press.

I manually fixed any suspect figures I found, such as the Chinese war epic which IMDb claims cost $18. (Incidentally, I noted this error four years ago and it’s still live – a healthy reminder as to the unreliable nature of publicly sourced data).

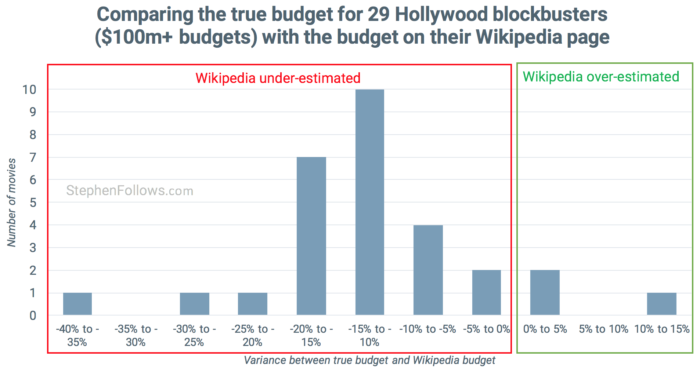

The publicly available figure should be regarded as a rough ballpark, rather than a precise number for a bunch of reasons. We can’t trace the original source of the figure, we don’t know if they are including soft money/rebates, the filmmakers may not be telling the truth, etc. A while ago, I gained access to the full, real costs and income of 29 Hollywood movies budgeted over $100m and so was able to compare their true cost with the figure stated on Wikipedia. I found that on average these movies cost 12.5% more than their Wikipedia entry stated.

I don’t know if this pattern is reflected in lower-budget movies.

It is difficult to know how many of the trends we’ve seen in the past couple of years are down to a reporting bias. It can take some time for budget figures to be released publicly, meaning that some of the films from 2021for which we do not yet have budgets will eventually have a figure. This is, in part, why I omitted 2022 in the charts above. If these missing budgets were unevenly distributed (i.e. more like to be lower-budgeted films) then this would depress the number of some budget ranges (i.e. such as showing a drop in lower-budgeted films). While there is likely to be a small amount of this at play, I do not think it’s significant, nor does it invalidate anything I have found today. A while ago I studied this phenomenon in relation to a decline in micro-budget productions in the UK, which the BFI suggested was partially caused by delayed budget discovery. I tracked how long it had taken budgets to be discovered in previous years, to assess the scale of under-reporting. More on that here What’s happened to UK low-budget film production?

I did not provide a time-series breakdown of the films reporting a budget of under $1 million as the data is not reliable enough to be meaningful, due to the factors mentioned above.

These figures do not take into account inflation. $1 in 2000 is the equivalent of $1.75 in 2023.

The years on the charts relate to their first public release. In some cases, films will have been shot a few years prior (so a “2021 film” could conceivably have been made entirely pre-pandemic) while others are rushed to market (meaning a “2020 film” might still have been made under pandemic conditions). If you want to learn more about (pre-pandemic) production lead times, you may enjoy this article How long does the average Hollywood movie take to make?

It’s worth noting that we have a lot fewer data points for the most recent years. Partly because of the pandemic halting most productions, as well as the budget factors listed above. This means it’s much less reliable and subjective to empty fluctuations.

Epilogue

I both love and loathe projects like this. I love the long-term trends and having to make sense of a number of different factors. I am not a fan of the huge amount of subjectivity which is needed to produce any result. Even just changing a couple of the decisions I made along the way could produce a different result.

If you feel I haven’t made the right call on some part of the process or criteria, please do add your voice to the comments. If there are big ones I can re-run the numbers for, I’ll happily do it.

At the end of the day, while today’s topic may sound like a simple question, I don’t think we can provide one simple, satisfying answer to which everyone will agree. Hence the horrible qualifications-to-charts ratio in today’s piece!

Comments

Very helpful, insightful, and well laid-out analysis presentation. Thank you Stephen! Great work!

I stayed until the end of Quantumania to watch the end credits. There were literally HUNDREDS of special effects employees for that movie. Not dozens. Hundreds. My jaw dropped at the “pages” and “pages” of names that rolled up the screen. There’s where these top budgets are blowing up. My movie only needs “special effects” for explosions, because they are cheaper to fake than permit and make.

I’m seriously considering just putting my first movie on youtube as a series of installments. It will showcase the use of my real patented prototypes to just barely save us from plummeting into WW3, so fighting my way into theatre distribution, and/or lost at the bottom of some Netflix play list, with just images of actor faces to “advertise” my dark comedy present day film, seems a total and complete waste of money and time. It’s the middlemen who make all of the money if you aren’t one of the very top studios.

Stephen, I live for these articles. I have been waiting for this follow-up for a few years. Can you do an follow up on low-budget UK movies?

Interesting stuff.

It’ll be interesting to see what the EUCD regulations now making annual payments (and in some cases back payments to 2008), will do to those figures. Certainly on state backed productions, it shouldn’t shift much, because fair pay is supposed to be embedded, but it will be interesting to see where the ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’ has been happening elsewhere.

What the heck happened in 2011?!

2011 had an uncommonly high number of superhero movies for the era, including the $200m Green Lantern, as well as Pirates of the Caribbean 4 (one of the most expensive films ever), and then bizarrely high-budget stuff like Mars Needs Moms, Cowboys & Aliens, Green Hornet, Three Musketeers… Maybe that’s part of it? I’d love to see Stephen or someone else do some kind of a rundown there because I’m really interested in that too.

I don’t understand the difference between the two:

1. “The first thing to note is that this is the average, meaning the total spent divided by the number of films made.”

2. “let’s track the median budget – i.e. the midpoint between all the budgets of each year.”

The difference between the two lies in how they represent the central value of a dataset.

1. The average, or mean, is calculated by adding up all the values in the dataset (in this case, the budgets of films made) and then dividing that sum by the total number of films. This gives you an overall view of what the typical budget might be, but it can be skewed by extreme values (i.e., very high or very low budgets).

2. The median is the midpoint in the dataset when the values are arranged in ascending or descending order. It represents the value that separates the dataset into two equal halves. In other words, 50% of films have a budget below the median value, and 50% have a budget above it. The median is less affected by extreme values, making it a more accurate representation of the central tendency for a dataset with outliers.

Comparing the average and median budgets helps to get a better understanding of the data distribution and see if there are any significant changes in film budgets over time.

Your website has saved me countless hours of searching for movie information. The reviews, release dates, and recommendations are spot-on. Keep up the excellent work!

Dear Stephen,

I aqm involved in adapting my autobiography. for the cinema. There are no inflated Hollywood salaries involved and only one name of any real importance in the cast, many of whom will make just one appearance. and then be seen no more. Have set a budget of 15 millon Euro. Do yoiu thimk That is enough?

Martin

From a low budget perspective, budgets are pretty much an ideal situation in my experience, it all depends on who will buy into the project to give you X amount. Also funding comes from multiple sources over multiple years, in some cases, which all adds cost.

Theoretically, it should be cheaper to make films, nearly everyone has a phone with a camera in their pocket that will be at least 720p. However, this lowering the bar has unfortunately flooded the market with lower quality. Filmmakers can produce a film for peanuts, that gets very lucky and hits the market at the right time, to become a success. The reality is 99% of them won’t.

It all comes down to the script. Filmmakers should draft and redraft. No amount of money will save a poorly executed idea to begin with.